Introduction

As countries and regions become increasingly multicultural, multiethnic, and multilingual (Jensen et al. 2021; United Nations 2020), the need for high-quality data on demographic subgroups has also grown (Willis et al. 2014). Such data is necessary to understand changes in population diversity, socio-economic shifts, and human rights monitoring (European Commission 2021; Willis et al. 2014). However, individuals with a migration background or who are members of ethnic minority groups are frequently underrepresented in survey research, due to a lack of extant sampling frames and statistical constructs which privilege more homogenous general population members in survey language, geographic accessibility, and availability (Nam et al. 2013; Yancey, Ortega, and Kumanyika 2006). A further challenge is that many ethnic minority groups are what Kalton and Anderson (1986) consider “rare”, i.e., they comprise less than 10 percent of the total population, even though – in aggregate – members of these demographic subgroups may comprise a sizeable percentage of the population (Destatis 2022).

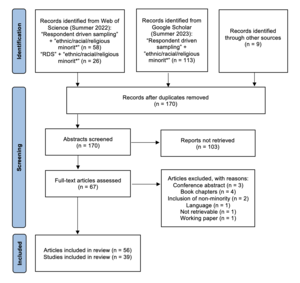

One increasingly popular method of sampling and recruiting ethnic minority individuals to research studies is respondent driven sampling (RDS; see Figure 1). RDS was developed in the late 1990s in order to investigate populations otherwise “hidden” from researchers due to lack of sampling frames (Heckathorn 1997). In an RDS sample, non-random “seeds”, i.e., members of the target population, are selected and asked to recruit further respondents from their personal networks, with an incentive provided to both seeds and recruits. Each seed and subsequent recruit is provided “coupons,” which serve as proof that the individual was recruited into the study through a personal network and to indicate the network chain to which they belong (Figure 2). Researchers can thus apply mathematical weights to partially compensate for the initial non-randomness of the seeds (Hipp, Kohler, and Leumann 2019).

RDS provides several advantages for including potentially vulnerable ethnic minority populations: recruited individuals have a higher likelihood of membership in the target population than respondents recruited via probability sampling (Lavallée 2014), and potential respondents are unknown to the researchers until such time as they choose to act on a referral. This reduces risk to both the respondents and the researchers, as the interview can take place in more neutral – and perhaps safer – locations such as public libraries, or even office spaces rented for the study purpose (Constantine 2010; Montealegre et al. 2013). Furthermore, advances in RDS methods allow for unbiased (point) estimates (Hipp, Kohler, and Leumann 2019; Lavallée 2014; Salganik and Heckathorn 2004).

However, in practice, RDS can be difficult to implement due to its “highly prescriptive” recruitment requirements (Waters 2014, page 3, see also Middleton et al. 2022): seeds and recruits must know each other; recruitment chains and relationships must be documented using coupons; the number of coupons provided per recruiter is limited; and all participants must report their personal network size. Additionally, extant literature often provides inadequate methodological details to support researchers in implementing new studies or troubleshooting complications (Avery and Rotondi 2020; Johnston et al. 2019; White et al. 2015). In the case of RDS with ethnic minorities, these challenges are further compounded by the limited research focused specifically on ethnic minorities.

This review intends to address this methodological gap by making explicit challenges resulting from these populations’ frequent economic, educational, linguistic, legal, political, and social vulnerabilities and identifying methodological adaptations necessary to successfully implement RDS with ethnic minority populations.

The Present Study

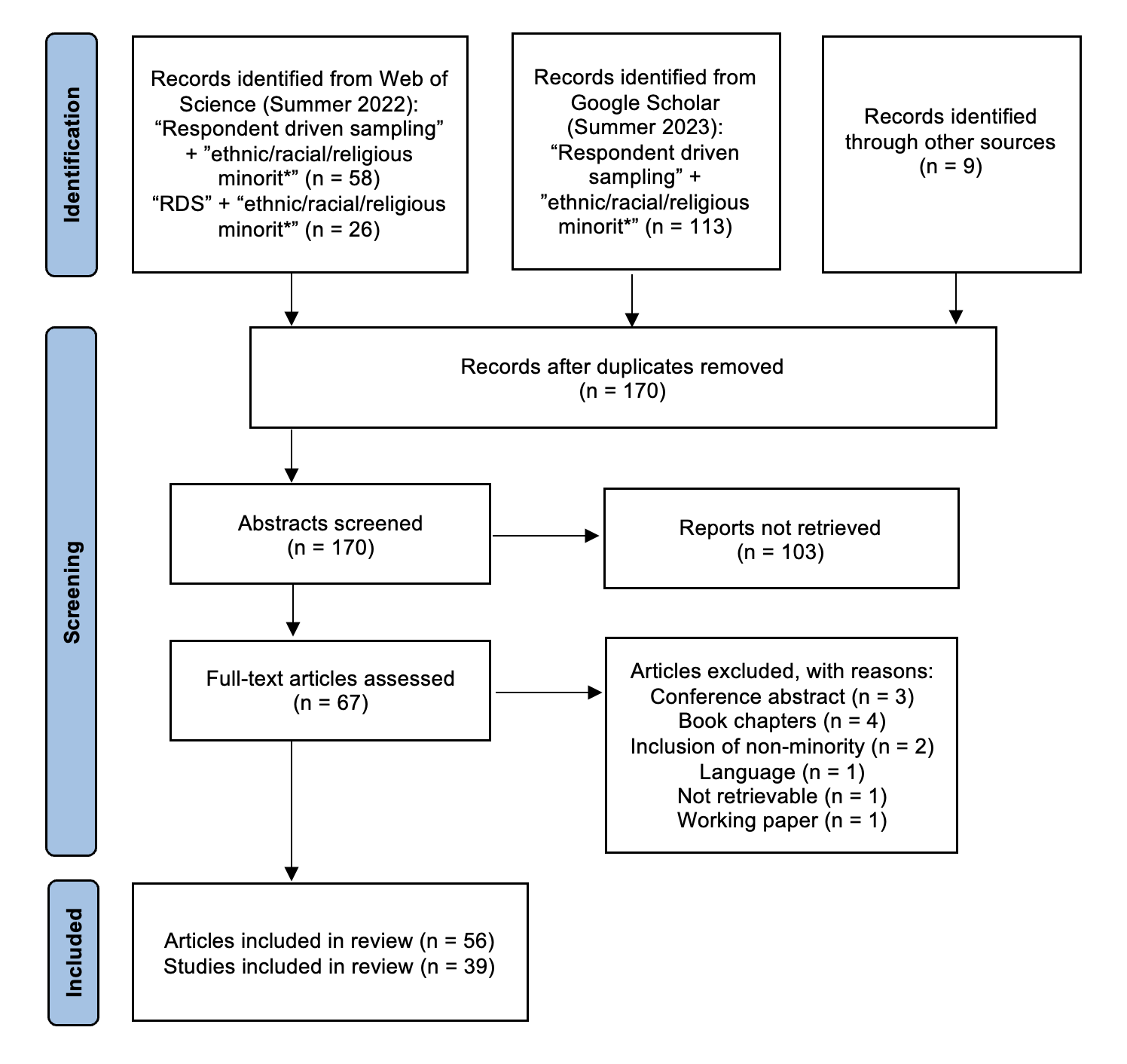

Between May and August 2023, I identified a total of 67 unique peer-reviewed journal articles through a combination of Web of Science and Google Scholar searches, previous literature reviews and outreach to colleagues (see Figure 3). Non-article results (e.g., book chapters, conference presentations), as well as articles not written in English, were excluded. Articles were included if they described original research (i.e., not reviews) which exclusively targeted ethnic or racial minority individuals for RDS recruitment to a study (n = 56). Multiple articles dealt with the same study. Despite overlap, I retained all eligible articles for review, covering 39 studies. Table 1 presents the included studies.

The earliest identified study was conducted in 2003 (Ramirez-Valles et al. 2005) with the most recent conducted in 2019 (Rivera, Carrillo, and Braunstein 2021; Rivera, Lopez, and Braunstein 2023; Sadlon 2022; Wirtz et al. 2021). The majority of studies (26) were published in public health-related journals, followed by methods-focused journals (5).

Studies ranged in duration from one (MacQueen et al. 2015) to 39 months (Franks et al. 2018) with an average of seven months. Six studies recruited fewer than 100 individuals, although three of these (Coombs et al. 2014; Henny et al. 2019; Vershinina and Rodionova 2011) were qualitative or pilot studies. Eighteen studies recruited more than 500 individuals, including three studies (four articles) which recruited more than 1000 individuals (Mizuno et al. 2012; Murrill et al. 2016; Wangroongsarb et al. 2011; Westgard et al. 2021). As shown in Figure 4, there appears to be no correlation between duration and sample size.

Twenty-three studies were conducted in the US, four in the UK, and two each in Canada, Germany, and Poland. The remaining six studies were conducted in further countries in South America, Europe, and South-East Asia. In the US, most studies focused on ethnic minority individuals who were also either sexual or gender minorities or engaged in behaviors of interest (e.g., fatherhood, immigration, transactional sex), as other methods of identifying members of larger ethnic groups (e.g., Black, Latino) are available. Of these, immigrants, particularly Latino immigrants (four studies) comprised the largest group (eight studies). Only three studies considered rare ethnic populations, such as Korean Americans (Lee, Ong, and Elliott 2020; Lee et al. 2021) and Burmeses refugees (He et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2018). In contrast, studies from non-US countries focused largely on individuals with direct migration experience; a quarter of studies (four) targeted non-migrant ethnic minorities: native Dutch of Moroccan descent (Hamdiui et al. 2018), indigenous Canadians (Rotondi et al. 2017), indigenous Ecuadorians (Mullo, Sánchez-Borrego, and Pasadas-del-Amo 2020), and Roma (Djonic et al. 2013).

Eight studies provided no information on incentives provided to either seeds or recruits. Following generally accepted practice (Liem and Hall 2020; World Health Organization 2013), most studies implemented a dual incentive scheme, in which all study participants receive an incentive, while recruiters receive an additional incentive for each individual successfully recruited. Incentives ranged from the equivalent of 5-75 USD for the participation incentive and 5-20 USD per recruit. Three studies (six articles) provided only participation incentives (approximately 5-60 USD). Franks et al. (2018) provided only a recruitment incentive (5 USD), while Mullo, Sánchez-Borrego, and Pasadas-del-Amo (2020) provided lottery tickets as incentives. Studies with the highest ratios of seeds to total sample (i.e., in which seeds make up a large proportion of those sampled) provided the lowest incentives (5-25 USD), but several studies with lower incentives still reported low seed/sample ratios (e.g., Denson et al. 2017; Franks et al. 2018; Górny and Napierała 2015; Weinmann et al. 2019).

Five studies (nine articles) conducted RDS as part of a larger community-based participatory research (CBPR) project. While four of these studies have some of the lowest seed/sample ratios (ranging from 1.0% to 8.9%), due to limited information about the role of CBPR in these studies, I am unable to draw any conclusions. Stronger evidence exists for the importance of formative research in ensuring successful implementation. Sixteen of the 21 studies which conducted formative research had low seed/sample ratios (ranging 1.0% to 11.7%). The one study which stated the authors did not conduct formative research (Evans et al. 2011) had one of the highest seed/sample ratios (85%).

In the next section, I discuss in further detail several factors which contribute to the likely success or failure of RDS studies with ethnic minority populations. Additionally, I provide practicable recommendations for researchers looking to implement such studies.

Discussion and implications for best practices

Recommendation 1: Conduct formative research and build trust in the pre-fielding phase.

Conducting formative research before fielding allows researchers to investigate whether the target population is in fact socially networked (Djonic et al. 2013; Platt, Luthra, and Frere-Smith 2015; Wirtz et al. 2021), as well as identify other potential barriers. Many ethnic minorities experience intersectional vulnerabilities such as poverty, poor health access, or unstable or poor living and working conditions, which may necessitate adaptations to the study design (Gilbert et al. 2018; Gilbert and Rhodes 2014; Montealegre et al. 2013). Formative research also provides an opportunity to build community trust and identify possible seeds (Ramirez-Valles et al. 2005; Rotondi et al. 2017).

Trust-building is essential for successful recruitment of minority groups (Gilbert et al. 2018; Górny and Napierała 2015; Weinmann et al. 2019; Westgard et al. 2021), due to harmful legacies of research and data collection (Nobles 2001). Researchers demonstrate trustworthiness not only through the development of community partners and relationships (Gilbert et al. 2018; Djonic et al. 2013; Rhodes et al. 2013), but also through thoughtful study design choices, e.g., using coupons which reduce risk to respondents (Rivera, Lopez, and Braunstein 2023; Montealegre et al. 2013), conducting interviews in neighborhoods or neutral spaces considered safe by participants (Hipp, Kohler, and Leumann 2019; Montealegre et al. 2013), and allowing respondents to participate in their preferred language (Platt, Luthra, and Frere-Smith 2015).

In this review, just over 60% of the 26 studies with seed/sample ratios under 25%[1] noted the use of formative research in the planning stage. While insufficient evidence is available to definitively state that not conducting formative research will result in high seed/sample ratios, Evans et al. (2011) do themselves make that argument.

Recommendation 2: Work with community partners to choose enthusiastic, diverse seeds with larger social networks.

Recommendation 3: Identify more potential seeds than necessary; additional seeds may prove useful if recruitment slows.

RDS, by definition, places the burden of recruitment on the study participants. Multiple studies noted the importance of good seed selection and training as factors in their success. Rotondi et al. (2017) found that diverse seeds selected in consultations with community partners were better able to engage the broader indigenous Canadian community and sustain recruitment through multiple waves. Rhodes et al. (2013) similarly note the importance of partnering with community organizations to select seeds. Gilbert et al. (2018) found that the most productive seeds were those who were younger and in better health. Lee, Ong, and Elliott (2020) also found a higher likelihood of coupon redemption among participants with larger networks. Furthermore, both Rotondi et al. (2017) and Lee, Ong, and Elliott (2020) found adding more seeds over time improved recruitment speed.

Recommendation 4: Provide translated study materials and/or trained bilingual interviewers when working with foreign language speakers.

Multiple studies cited possible language barriers as reasons for low response among migrant populations (Montealegre et al. 2013; Tyldum 2021; Weinmann et al. 2019). However, low fluency in the destination country language does not mean that target individuals have low literacy rates in general; Wangroongsarb et al. 2011 noted that while Cambodian and Burmese refugees in Thailand had low Thai literacy, they had sufficient native language literacy for written study materials to be of value.

While surveying participants in their preferred language does not guarantee high response rates (Hipp, Kohler, and Leumann 2019; Lee, Ong, and Elliott 2020; Lee et al. 2021), it does appear to improve response as well as diversify participants, thereby reducing selectivity bias (Evans et al. 2011; Denson et al. 2017; Hamdiui et al. 2018; Gilbert et al. 2018; Lee, Ong, and Elliott 2020).

Recommendation 5: Distribute appropriate incentives.

The determination of appropriate incentive amounts, particularly with vulnerable populations, can be ethically fraught (Liem and Hall 2020; Singer and Bossarte 2006), and is outside the scope of this review. Only two studies noted specific factors considered: average hourly wage of target population (Górny and Napierała 2015), and burden (time, cost) of participation (Evans et al. 2011). Similar to Johnston et al.'s (2008) findings, neither the absolute monetary value nor the type of incentive scheme (dual vs. participation only) appears definitively correlated with success. Several studies with lower incentives still reported low seed/sample ratios (e.g., Denson et al. 2017; Franks et al. 2018; Górny and Napierała 2015; Weinmann et al. 2019). Furthermore, Kogan et al. (2011) found that participants were motivated more strongly by helping their friends receive incentives than the recruitment incentives.

Recommendation 6: Design coupons appropriate for the habits and vulnerabilities of target populations; use virtual coupons (webRDS) as a default.

Only five studies (six articles) used virtual coupons; two of these (Hamdiui et al. 2018; Wirtz et al. 2021) in combination with physical coupons. However, implementation of webRDS does not appear to be negatively associated with recruitment success. In fact, Lee, Ong, and Elliott (2020) and Lee et al. (2021) report high success with virtual coupons; the Korean Americans sampled shared coupons via popular messaging apps, email, and phone conversations, allowing participants to recruit network contacts who were more geographically dispersed. Furthermore, they found that 27.3% of participants shared coupons using multiple modes (Lee, Ong, and Elliott 2020) and that younger recruits were more engaged with the virtual coupons (Lee et al. 2021). Rivera, Lopez, and Braunstein (2023) also found that virtual coupons allowed seeds to recruit a wider range of contacts.

The use of virtual coupons also removes the necessity of printing sufficient coupons in multiple languages (Evans et al. 2011). As with other study materials, providing coupons in the recruit’s preferred language reduces barriers to recruitment, increasing the likelihood of success (Lee et al. 2021).

Finally, virtual coupons reduce the risk of outing vulnerable populations, as there is less risk of the coupon being discovered (Montealegre et al. 2013; Rivera, Lopez, and Braunstein 2023). The use of webRDS, including conducting the survey online, is an increasingly productive method of recruiting rare or vulnerable populations (Evans et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2021) by removing barriers such as irregular schedules and the necessity of operating in a non-native language or with a translator (Gilbert et al. 2018; Montealegre et al. 2013).

Conclusion

This article presents the results of a scoping review of RDS studies with ethnic minority populations. I find that it is possible to conduct successful RDS studies with a range of ethnic minority populations, including specific subpopulations such as sexual and gender minorities and immigrants. I also identify several factors contributing to the likely success or failure of such studies. While factors such as mode of survey, incentive amount and type of scheme (dual vs. participation only) do not correlate strongly to high sample response, the use of native-language materials, seed selection, and degree of community trust do appear to improve both survey response and sample diversity. Multiple studies noted the importance of formative research to build trust and inform study design, including on elements such as study language, incentives, and coupon design and mode. Some of these themes echo Theorin and Lundmark’s (2024) focus group study of immigrants in Sweden as well as Singh et al.'s (2018) systematic review of ethnic minority retention. Based on these findings, I provide six recommendations for implementation.

While this article addresses the methodological gap for practicable guidance for implementing RDS with ethnic minority populations, more research must be conducted. Furthermore, authors of such research should follow the STROBE-RDS guidelines (White et al. 2015). The need for high-quality data for ethnic minority populations and other demographic subgroups will only continue to grow with time, and so must our knowledge base of ethical, practical, and reliable methodological solutions.

Lead author’s contact information

Mohrenstraße 58, 10117 Berlin, Germany

An arbitrary cutoff, but one indicating that on average, each original seed ultimately produced three recruits.