Introduction

Survey researchers depend on both the reliability and validity of the responses to the questions in their survey instrument to ensure data quality and utility. An effective questionnaire is also necessary to minimize respondent burden, since confusing questions may cause the respondent to feel uncomfortable in the interview and less confident in their answers. Consistency and clarity of question text are recognized as necessary to achieve high quality data (Olson, Smyth, and Ganshert 2019), but the care and consideration given to the source questionnaire is rarely afforded to its translations, which can introduce non-sampling error (Harkness 2011), impacting total survey error (TSE) (Groves and Lyberg 2010).

Those working on multilingual surveys have called for quality translations that prioritize construct validity over direct translation (Silber et al. 2022). This requires considering language early in the process of developing the questionnaire. Doing so enables inter-language and inter-cultural adjudication and decision-making, improving all questions efficiently (Dorer 2022; Harkness, Pennell, and Schoua-Glusberg 2004; Harkness and Schoua-Glusberg 1998). To ensure greater inclusion while recognizing the power dynamics inherent in data collection, researchers can approach survey translation through the lens of language justice. This framework aims to decenter the dominant language and instead prioritize an immersive experience in one’s preferred language (Arguelles, Williams, and Hemley-Bronstein 2012).

Not only does team translation outperform other methods for accuracy and fluency but addressing inter-language issues prior to finalizing the source questionnaire improves the translatability of an instrument both linguistically and culturally (Behr and Braun 2023; Dorer 2022). Advance translation utilizes initial translations of a source questionnaire to enable an interdisciplinary team of survey methodologists and language specialists to adjudicate issues (Dorer 2022). This method has been used by the European Social Survey (ESS); however, it is most successful in the context in which it was developed, i.e., to ensure equivalent instruments in the official languages of a cross-national survey. In the United States (U.S.), where there is no official language and where most non-English speakers belong to immigrant communities, survey researchers face different challenges. Chief among these are differential power dynamics, timing of (and age at) immigration, education levels, and regional dynamics that manifest in language. Advance translation still represents the best approach but requires adaptation to address these issues. In this paper, we describe one approach used in a survey of New York City’s housing and community-dwelling population.

Language Diversity

In New York City, 46% of residents speak a language other than English and a half of them— 23% of the overall population—have limited English proficiency (LEP).[1] More than 200 languages are spoken in the city (City of New York 2022). A survey designed to be representative of this population must account for languages other than English.

There is diversity within languages in New York City in addition to across languages. Understanding the source and type of variation within the population who speak a target language enables the survey team to address differences across country of origin, time of immigration, and age cohort. Figure 1 illustrates the LEP population in New York City for Spanish-speakers by region and Chinese-speakers by years since immigration.

There are 1.8 million people who speak Spanish in New York City (23% of the population).[2] Of those born outside of the U.S. and Puerto Rico, the largest population of Spanish-speaking immigrants is from the Dominican Republic. Almost 150,000 New Yorkers from the Dominican Republic are LEP, greater than the city’s entire population of Spanish-speaking immigrants from Mexico. If we were to ask about public commuter buses a translation for immigrants from Mexico might refer to “bus” as a “camión,” but a translation for immigrants from the Dominican Republic would use the term “guagua.” If we were to choose the term best suited for the largest population (Dominicans), we could introduce additional confusion, since for immigrants from Chile, the term “guagua” refers to a baby. As immigrants live in their new community longer, they gain familiarity with local terms, resulting in diversity of understanding within a linguistic community. The Chinese-speaking population in New York City varies substantially by time of immigration, which may result in differential adoption of English terms. While LEP is often the primary motivator for translating surveys, bilingual populations may have unique language needs and surveys should not default to English (Goerman et al. 2019). A principle of language justice is to facilitate an immersive experience in one’s preferred language, enabling each respondent to express themselves as they choose.

NYCHVS Translation Approach

Advance translation was first implemented by the ESS to ensure quality and parity across countries and cultures. The standard process consists of a cyclical methodology of review and decision making. Using an initial draft of the questionnaire, at least two translators produce independent translations and categorize problems that represent barriers to linguistic and cultural equivalency (e.g., intercultural problem/cultural difference, unclear meaning/difficult to understand, and grammar) (Dorer 2022). Problems are reviewed and discussed by translators and survey methodologists in consensus meetings and resolved by either adjusting the source instrument or altering the approach to translation (or both). Additional rounds of consensus meetings occur when appropriate. All questionnaires, across all languages, are developed simultaneously. The ESS advance translation is optimized for the European context, where there is a need for translation into dominant languages of participating countries to ensure consistency across the continent.

The NYCHVS has been conducted by the city about every three years since 1965, contracting the U.S. Census Bureau as its data collection agent. As part of a redesign in 2021, the survey team evaluated the prevalence of LEP across the most common languages in the city and committed to formal instruments in English, Spanish, Russian, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, Haitian Creole, and Bengali.[3],[4],[5] Although our advance translation process focused on written language, language access was incorporated into training, which included spoken aspects, such as Mandarin and Cantonese (Sha and Immerwahr 2018).

For the 2021 NYCHVS, the survey team and the U.S. Census Bureau adapted the advance translation process. We began using a team of remote translators under the Census Bureau’s translation contract, aiming to follow the ESS process for our selected languages. Utilizing a remote translation team proved challenging and ultimately led to further adaptations of our approach (Goerman 2022). As discussed above, it is essential to understand the nuanced differences within the target population of speakers of nondominant languages and to recognize the preferred dialects within the target area. For a remote team of translators unfamiliar with New York City, it was challenging to develop translations with these cultural factors in mind. Translation contracts are generally structured to be paid per word rather than per hour, so additional time spent considering each question fell outside the incentive structure. It was also challenging to ensure participation in consensus meetings, as translators are often contracted across time zones.

To address this, the survey team hired an in-house local language team to review the initial translations and participate in the process, including flagging barriers to translation and attending consensus meetings (Goerman et al. 2021). The team comprised two translators for each language. The survey team prioritized hiring a diversity of native speakers who lived and worked in New York City. The language team received both the source questionnaire and translations from the remote translators, but quickly discovered that the initial translations did not adequately identify linguistic and cultural issues that would arise in New York City. To address these limitations, each of the two members of each local language team worked independently to review the source instrument, essentially restarting the advance translation process. Throughout this process, we learned what steps could be adopted directly from the ESS methodology and what needed to be adapted to address non-dominant languages translated simultaneously.[6] Below, we describe the process we ultimately employed and lessons learned.

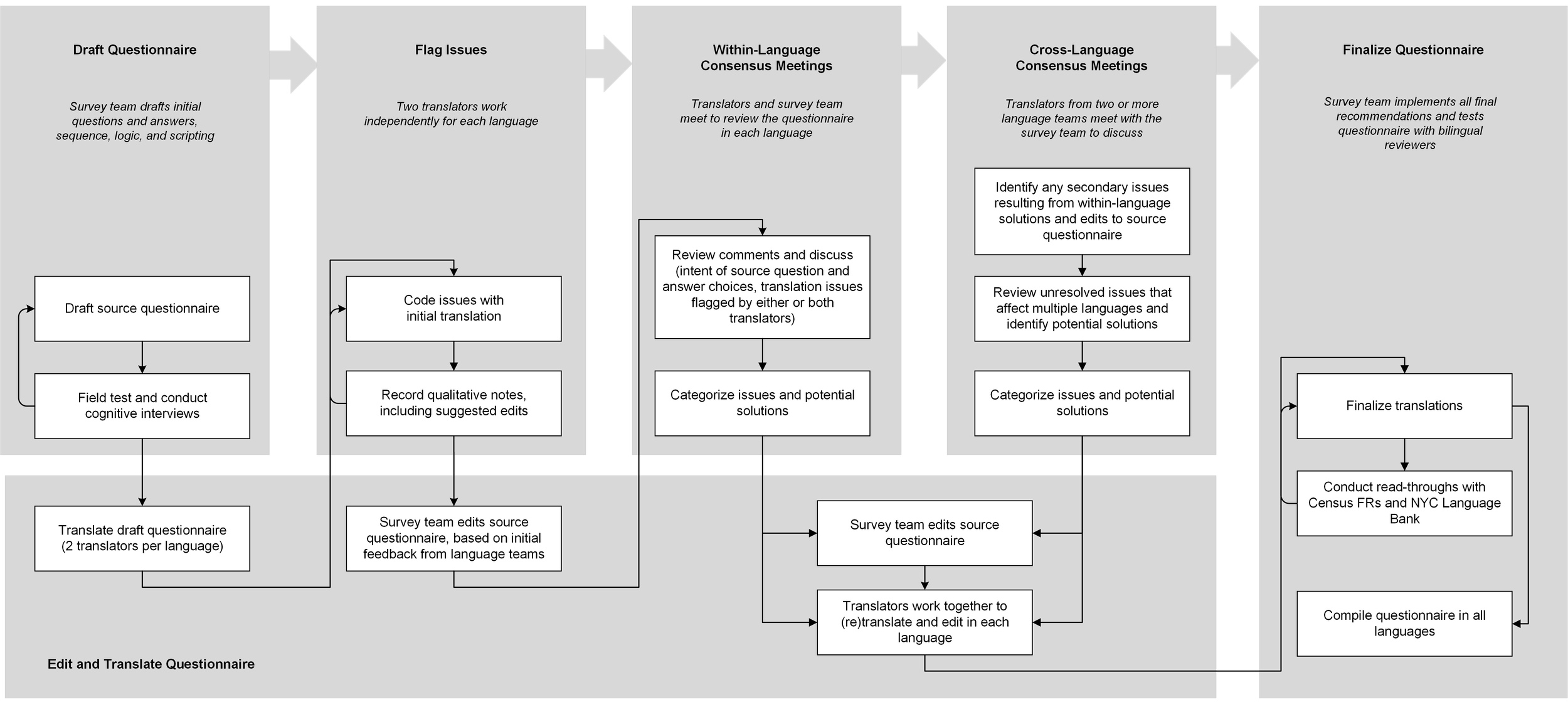

NYCHVS Advance Translation Process

Our advance translation process was implemented in phases, as outlined in Figure 2. The language team reviewed each question and coded barriers they identified in the translations and/or the source questionnaire. Their comments and questions did not always fit neatly into a problem category provided, so the survey team gave them the flexibility to write qualitative notes and suggest edits. The survey team reviewed and categorized notes to organize discussions.

After the initial review, the language team and survey team met in consensus meetings to discuss issues, including both the pre-defined categories and those that emerged from qualitative notes. Consensus meetings were conducted with the translators (and sometimes additional language resources), by language. Each group moved through question by question, discussing barriers, identifying emerging patterns, and marking potential solutions. If adjusting the translation was proposed, the language team worked together to implement the change. If, instead, the proposed solution was to adjust the source questionnaire, the survey team edited and tested the changes before handing it back for translation. Table 1 provides examples of each type from these within-language consensus meetings.

Within-language consensus meetings and corresponding edits were followed by cross-language consensus meetings. These had more specific aims, such as discussing whether potential solutions in the source questionnaire would work across all target languages. We again identified problems and proposed solutions, which were implemented either by the language team or by the survey team before handing an edited source questionnaire back for translation. Each language team worked together to implement changes and discuss translations, often retranslating large sections of the initial questionnaire as well as additional edits from consensus meetings. In doing so, the language team brought their knowledge of the intent of the question as well as the context of how their translation would potentially impact other languages.

The source questionnaire and translations were edited after each round of consensus meetings. This process continued until all barriers were discussed and adjudicated. For the 2021 NYCHVS, the advance translation process occurred simultaneous to ongoing field tests, which also informed improvements to the questionnaire. After many rounds of review, the seven instruments were finalized and reviewed by bilingual employees from New York City’s Volunteer Language Bank[7] and bilingual U.S. Census Bureau field representatives.

One of the major shifts in our process was the ongoing collaborative nature of the team working in tandem and open lines of communication among and between the translation and survey teams. Having an in-office team meant that confusion about question intention or scope could be clarified immediately by the survey team between consensus meetings. The ability to discuss in real time increased efficiency and promoted collaboration. Discussions between members of the language team from different regions, social classes, and age groups were not always easy and highlighted differences within their own linguistic community as well as the individual experiences they brought to the process, leading to more inclusive solutions. They debated the best approach, asking their broader network for feedback and suggestions when appropriate to come to agreement.

Outcomes and Recommendations

Advance translation improved the NYCHVS instruments in all languages, including English, with substantial changes in the source questionnaire and edits to almost every question. Often the process prompted us to ask, “What is the intention of the question? What are we hoping to learn?” By revisiting our answer, the survey team was able to collaborate with the language team to arrive at solutions that worked while still maintaining the question’s core function. Many researchers begin by selecting questions used in other surveys to replicate, but translations for these questions are rarely available in more than one or two languages, if at all. Our experience underscored the importance of developing or modifying existing questions to address the local context and needs of the survey.

Advance translation often demanded simpler phrasing, with direct questions and no ambiguity. This was especially important for languages like Spanish and Russian, which tend to have longer phrases that quickly become too long to read out loud naturally. The process also led the survey team toward using plain language rather than conversational or more formal phrasing. Within the interview environment, clarity and conciseness were more important than trying to set people at ease. As a result, almost all scripts from the questionnaire were removed to avoid unnecessary text.

Additionally, changing the source questionnaire was often not the best option. The most intuitive phrasing for a survey construct in another language may not have an equivalent in English, so after many debates, the survey and language teams concluded that non-verbatim translation may sometimes be the most appropriate choice. This gave the language team freedom to use plain, clear language without always being tied to direct English translation. Embracing phrasing that is unique to a language, including questions stems and answer choices, also meets the intent of language justice, which seeks to decenter English and to treat all language communities on their own terms.

Lessons learned during advance translation impacted the way the survey team approaches questionnaire design, including question structure and terms commonly found in surveys. For example, members of the Simplified Chinese language team brought up the issue that Likert-scales were difficult to translate with consistent nuanced spacing between each answer option across languages. Instead, the survey team replaced them with 1-10 numeric scales, which were agnostic to language. The team also removed common terms that do not have equivalents in other languages, such as “household” and “unit,” and opted instead to ask about “you and the people you live with” and to let respondents choose whether to refer to their homes as an “apartment” or a “house.” This had the additional benefit of achieving clarity across cultures, regardless of language.

Conclusion

Advance translation for the 2021 NYCHVS not only improved the questionnaire, but also changed the way we approached survey design. While the process required substantial resources at the outset, the benefits reverberate into the future, with alterations to the source questionnaire benefiting subsequent survey cycles and easing translation into additional languages.[8] For this reason, we advocate for advance translation during survey redesigns or the development of additional survey modules.

For the NYCHVS, the team developed instruments in each of seven languages, which targeted the LEP population in New York City. These languages have their own variation within their speaker population, including by region of origin, time of immigration, age, and education; advance translation helps address this. The NYCHVS advance translation effort principally differed from the ESS in that it was aimed at non-dominant languages in a single multilingual city, rather than the many dominant languages across a diverse continent.

The utility of advance translation is clear for linguistically diverse metropolitan areas containing large non-English speaking populations with variation both across and within languages. But advance translation can also serve the key role of finding neutral language. Rather than using consensus meetings to target the questionnaire to a specific population, survey teams can engage practitioners from a wide range of backgrounds to identify language that may (dis)advantage certain groups. In this context, advance translation ensures not only equivalency in multilingual surveys, but also accessible, inclusive language that speaks to, and empowers, the population represented in our data.

For the NYCHVS survey team, advance translation illuminated the necessity of incorporating language into all survey plans. These practices align with the principles of language justice, developed and practiced by language practitioners, organizers, and advocates (Antena Aire 2020; Arguelles, Williams, and Hemley-Bronstein 2012; Lee et al. 2019; Tang Yan et al. 2022). These principles apply to the entire survey lifecycle, since the success of surveys relies on full participation of all sampled respondents. We have separately discussed the application of these principles into our materials, recruitment, and training in “Multilingual Communities Require Multilingual Surveys: A Language Justice-Informed Approach to the New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey” (Waickman and Corbett 2022). Questionnaire translation should fit seamlessly together within this broader language justice approach to the respondent experience. If we are going to decenter English in surveys, we need to think about language justice in all phases of the work—not only recruitment and questionnaire design, but also documentation and dissemination of findings. As we incorporate language justice into our work, we improve the quality of our surveys and reach a wider group of both participants and data users. An adapted advance translation is one step toward this end.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Patricia Goerman and Mikelyn Meyers for their contributions to the conceptualization and design of the initial phases of this project and Brita Dorer for her consultation on adapting the Advance Translation method to fit the context of this study.

Lead author contact information

Caitlin Waickman

waickmac@hpd.nyc.gov

100 Gold St. 5B10 New York NY 10038

These statistics are estimates from the 2023 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey (NYCHVS), NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Estimates represent the community dwelling population of New York City.

These statistics are estimates from the 2023 NYCHVS, NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Estimates represent the community dwelling population of New York City.

Translations were selected with written language in mind. For Chinese, this included translation into both Simplified and Traditional Chinese. These two written languages are used for a variety of dialects from regions across China and surrounding areas, most commonly in New York City Mandarin and Cantonese.

The decision-making process utilized the most up-to-date representative data on New York City at the time, specifically 2017 1-year American Community Survey data. The prevalence of most common languages is stable, and this selection of languages has been validated with subsequent data.

Local Law 30 of 2017 in New York City requires translation of commonly distributed documents into 10 designated languages (including the target languages of the NYCHVS) and telephonic translation in 100 languages. Though our survey is not subject to this law, it ensured wider buy-in from leadership about the importance of language access and socialized some of the issues implicit in our advance translation process. It is important to note, though, that this local law is generally implemented using a local translation contract and/or machine translation, such as Google Translate. These services do not meet our quality expectations for survey translation.

The remote team did not participate in meetings, review, or translation after passing the source questionnaire and draft questions to the language team in New York City.

NYC’s Volunteer Language Bank is a database of city employees across the city’s agencies who speak a language other than English and who volunteer their time to assist with language access.

While the advance translation was beneficial to our team, it took more time and resources than were originally anticipated. It resulted in cost savings in other ways, including imputation. For large scale surveys, we believe this cost evens out. The advance translation process for the NYCHVS added about 1.2% to the overall budget.

_and_limited_.jpg)

_and_limited_.jpg)