Literature Review

There are a number of reasons to take particular care with sociodemographic questions, which allow researchers to describe their sample as well as to determine if these characteristics are associated with people’s behavior (Hughes et al. 2016). Among the most commonly used sociodemographic questions in surveys are education level, race, ethnicity, and age (Hughes et al. 2016). Researchers often invest significant resources into ensuring that new survey questions are well tested through cognitive and field testing. This includes translations, which are ideally reviewed and tested as well.

However, key sociodemographic questions are often treated as “set in stone” by survey designers and they continue to use prior wording, which is considered “tried and true,” because of concerns such as time series continuity and use of data from other surveys for benchmarking and weighting, for which changes to question wording would be problematic (van den Brakel, Smith, and Compton 2008). Challenges exist in comparability of survey questions across different contexts, particularly in cross-national surveys. There may be questions that work in one context but do not work in other contexts, especially when added without any pretesting. Context has a major role to play in considering the meaning and the phrasing of the question (Braun and Harkness 2005). Researchers use sociodemographic variables to segment samples, since they often function as basic independent variables used to organize analysis. Measurement error in key sociodemographics can seriously affect findings. For example, findings may show that level of education correlates with a behavior or attitude. The observed correlation may be weaker than expected if respondents are misclassified, because of how the education question is formulated, translated, or interpreted.

Researchers and subject matter experts strive for translated survey questions to be “equivalent” to the source question. But equivalence can mean many different things. In the case of translated questions, they should say the same thing as the original item, mean the same thing, measure the same constructs with similar scale, impose similar burden on respondents, and meet reliability and validity requirements. This is a tall order for the translation task. However, over time an effective translation methodology has been developed for that task – the Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pretesting, Documentation (TRAPD) approach, which delineates best practices for steps to complete when aiming for parallel survey translations (Behr and Braun 2022; “Cross-Cultural Survey Guidelines: Guidelines for Best Practices in Cross-Cultural Surveys” 2016; Harkness 2003; Pan, Sha, and Park 2019).

Many U.S. sociodemographic questions are deeply rooted in how we classify people in the U.S. These classifications do not necessarily match classifications in respondents’ cultures of origin. Classification schemes are not universal (Schneider, Joye, and Wolf 2016). For instance, education is a background variable widely used in different countries and most surveys include a question or variable about education. Education questions generally include response choices reflecting how the educational system is organized in a particular country, which can differ greatly from one nation to another. Race and ethnicity, on the other hand, are not widely used concepts; some countries include at least one in their key surveys and many others do not. A 2021 report found that 20 of 28 Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries, including Japan, Germany, France and Italy, do not collect information about race. Educational attainment, race and even age, can be understood differently in different cultural and linguistic contexts, leading to measurement error.

This paper focuses on known translation issues with some key sociodemographic questions. These questions use the same wording across many surveys and survey sponsors can be reluctant to make changes when a new survey instrument is created. We focus on questions about education level, race/ethnicity, age/date-of-birth, and names, a less often discussed but no less important variable. We conclude with a discussion of how to best address these issues.

1. Education questions

With a large percentage of the U.S. immigrant population educated abroad, the education variable presents particular difficulties for accurate data collection. There are well documented translation issues with education questions (e.g., Goerman, Fernández, and Quiroz 2018; Schoua-Glusberg, Carter, and Martinez-Picazo 2008). For example, for Spanish-speakers in the U.S., immigrants come from countries where the same language is spoken, but where there are differences in education systems and the terms used. In some cases the same terms are even used to refer to different levels of education across countries.

U.S. researchers often differentiate between respondents with and without a high school education. If “high school” is translated as used in Puerto Rico, with “escuela superior,” other Latin Americans will have never heard of that, except in the phrase “educación superior,” which refers to university studies. If “high school” is translated as used in Mexico, the term “preparatoria” is unknown to other immigrants. If “high school” is translated as used in the rest of Latin America, as “escuela secundaria,” for many Puerto Ricans, the reference may be unclear, and Mexicans may believe it is asking about completion of 9th grade rather than 12th grade as intended. Using “escuela secundaria” can also cause Mexican-origin respondents to report a very common educational attainment of 9 years of schooling as having completed “high school,” which is inaccurate.

Similar problems appear when translating “bachelor’s degree.” If we use the Puerto Rican term, ‘bachillerato,’ most other Spanish speakers will interpret the response category as having a high school diploma. Hidden misunderstandings of terminology can easily occur, with the effect of respondents unknowingly over-reporting their education level (Goerman, Fernández, and Quiroz 2018).

2. Race/Ethnicity Questions

Another key sociodemographic variable in the U.S. is race/ethnicity. Many countries do not use such a variable and this concept therefore has no social reality for many immigrants in their languages.

In the U.S., “race” refers to a classification of people based on physical appearance, social factors and cultural backgrounds (NHGRI “Cross-Cultural Survey Guidelines: Guidelines for Best Practices in Cross-Cultural Surveys” 2016). “Race” is typically translated into Spanish as “raza.” The term “raza” is not used in a parallel way to the U.S. concept of race in most Spanish-speaking countries. In Mexico, for instance, raza is not used to classify a person but to describe the collective ethnicity of a people born out of the historical mixing of indigenous peoples and Spanish conquerors. For other Latin Americans, the term “raza” is only used to refer to an animal’s breed. And yet, there is no other widely recognized parallel Spanish word for “race.” Cultures that use such a concept for social classification of humans have their own particular response choices, because the concept is based on a different cultural and historical context. Thus, response choices meaningful to the prevalent U.S. classification system do not work for some immigrant groups.

Behavior coding is a method in which exchanges between interviewers and respondents are recorded and then coded to see whether interviewers read questions exactly as worded and whether respondents choose the available response options without requiring extra assistance. A 2007 behavior coding study was conducted of the Census Bureau’s Hispanic origin and race series, with 54 English and 18 Spanish language doorstep interviews recorded and analyzed. The two-part question appears in Figure 1.

Results showed that Spanish-speaking respondents more often struggled to respond as expected with a yes or no response to the Hispanic origin question than did English speakers (Childs et al. 2007). In terms of the race question, more Latino respondents, both English and Spanish speakers, had difficulty choosing one of the provided response options. Some types of unexpected responses included “Hispanic,” “Latino,” or “Chicano,” which were not response options to the race question, or replying “I don’t know.” Other unexpected behaviors included describing oneself as “American” and using terms such as “moreno” or dark in response to the question. Interestingly, Spanish-speaking respondents more frequently had discussions with interviewers about their confusion rather than simply responding, which could indicate confusion and/or discomfort with what was being asked. There was evidence that the concept of a race question with the provided response options was not something with which respondents were familiar. Researchers concluded that many Latino immigrant respondents were more comfortable responding with a nationality than with one of the Census race categories.

3. Age/Date-of-birth questions

Contrary to what researchers might expect, qualitative research across languages has found a number of difficulties with questions on age and date-of-birth. Past research has found that Chinese speakers sometimes count age differently than people from other cultures (Wang et al. 1998). A newborn is considered to be 1 year old and then 1 year older each year at the time of the Chinese New Year celebration. When Chinese language translations are worded as in English, ages might be inconsistently reported across languages, which can have an impact on correlations between age and survey outcomes.

In terms of date-of-birth, it can be easy for an adult reference person living with nuclear family members to provide complete dates-of-birth for all household residents. Complex household living, where unrelated housemates or multiple families live together, is a common arrangement among new immigrants and the rates of complex household living vary a great deal by race/ethnicity, with Hispanic respondents being much more likely than non-Hispanic whites to live in a complex household (Jensen et al. 2018). In a complex household it is less likely that one respondent will know complete date-of-birth information for all household residents. Such respondents have been seen to invent birthdates after approximating the age of roommates (Jensen, Roberts, and Rogers 2023).

4. Names

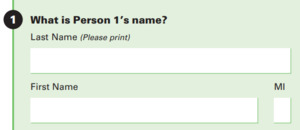

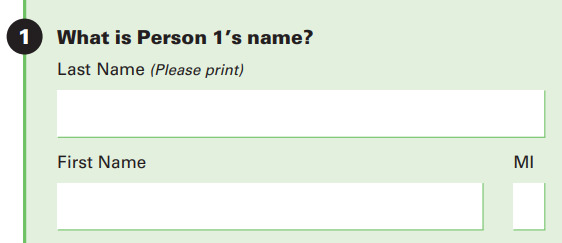

The request for names of all household residents, used for creating a household roster, can be complicated across language groups. Census Bureau surveys often ask for names in the following format.

Not all cultures have the same naming conventions as in U.S. English. For example, Spanish speakers often have names structured as follows:

Similarly, the structure of Russian names is first name, patronymic, last name. (Patronymic being a derivation of one’s father’s first name.) One study revealed that Russian speakers were confused when asked about their “middle name” (Isurin, Pan, and Lubkemann 2014). Although being placed between first and last name, patronymics are not equivalent to a middle name. Most Russian immigrants drop their patronymics, which can cause confusion when filling out U.S. surveys that ask for a “middle name.”

Automated instruments without space for two surnames or for a full second or middle name, as opposed to an initial, can be problematic. Names are often used for matching when administrative records are used to fill in the blanks due to non-response or to link multiple datasets that include different information. If respondents are asked to list their names in ways inconsistent with how they typically think of themselves or that differ across surveys, they are less likely to have their name listed consistently across surveys, which would allow them to be included in linked data sets. This could lead to differential rates of missing data across groups.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Rather than taking the traditional approach of translating “tried-and-true” question wording for sociodemographic questions, we argue that it is better to think cross-culturally about what concept one is trying to measure first. Ex-ante harmonization methods such as adaptation, parallel design across languages and advance translation, where the source language version is modified during the translation process, can create questions that have relevant meaning across languages as opposed to functioning just as “translations.” When not possible to employ these methods, we recommend rigorous exploration of whether a concept works as translated, and respondent testing is a key method for doing this. Solutions to this issue may be hard to come by, but it is important to document where cultural mismatches may arise to help avoid inaccurate conclusions from our data.

Regarding cognitive testing approaches, simply asking if a question was easy or difficult to understand or answer is not enough. Researchers should examine whether respondent narratives about themselves validate their responses to sociodemographic questions to uncover any hidden issues. The wording of basic sociodemographic questions should be carefully considered to meet measurement objectives, particularly when it comes to translations that may never have been tested. Failing to do this can be a threat to parallel data collection and interpretation.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau.

Lead author contact information

Patricia Goerman

U.S. Census Bureau

patricia.l.goerman@census.gov