A. Introduction

India, like many Low-and-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), has seen a massive growth in the penetration of cell phones, with more than 90% of the households having a mobile phone (Mohan et al. 2020). This expanded coverage offers an alternative to expensive in-person data collection (Dabalen et al. 2016), allowing social researchers to efficiently study the country’s large and diverse population. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of phone surveys in LMICs (where it was the preferred survey mode during that time; United Nations and World Bank 2020, 15) including India (Nagpal et al. 2021). This has likely resulted in a more sustained usage of this mode (Gourlay et al. 2021).

However, the socio-cultural and economic environment in India presents challenges in implementing phone surveys. In many households, cellphones act like landlines in that household members share a single number. Moreover, access to cellphones is gendered. The National Sample Survey (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation 2023; Waghmare 2024) reports that while 50% of the adult male population had exclusive use of a cellphone, this percentage drops to 40% for adult women. Fears of digital harassment, combined with traditional gendered norms and roles, mean that men may be sensitive to calls coming to women in their households. In a qualitative study, Giorgia et al. (2018) found that mobile phones in India are viewed as a ‘risk to women’s reputation’. While reputation concerns ease for married women, phone use in such cases is viewed as a barrier to a woman fulfilling her family responsibilities.

In such a situation, recruiting women respondents for a telephone survey can be difficult. In two surveys in India, Hersh et al. (2021) found that men pick up calls 63% and 71% of the time and pass the phone to women less than 11% of the time. This ‘gatekeeping’ (i.e., the explicit or implicit barrier to accessing the selected respondent) presents at least three issues. First, it can reduce response rates for surveys of women by reducing their participation. Second, systematic differences between respondents and non-respondents due to gatekeeping can lead to non-response bias. Third, some gatekeepers might refuse access to the specific selected woman respondent (especially if the survey content is sensitive) but offer to provide responses on behalf of the woman respondent. Such proxy responses can result in biased estimates (Badoe and Steuart 2002; Davin, Joutard, and Paraponaris 2019).

The literature on gatekeeping in telephone surveys globally is sparse, likely because it is a culture-specific phenomenon brought to light only recently by advances in mobile access. Brubaker, Kilic, and Wollburg (2021) examine biases arising from respondent selection in telephone surveys but do not mention issues with gatekeeping. Hersh et al. (2021) specifically deal with gatekeeping, describing their experience from surveys in India. We build on this initial work and contribute to the literature in the following three ways: first, we estimate the prevalence of gatekeeping; second, we use call record data and examine different types of gatekeeping and their association with non-response and proxy interviews; and third, we model the likelihood of the occurrence of a proxy interview as a function of household, respondent, and interviewer-level variables.

B. Survey

The India Human Development Survey (IHDS) is a large-scale pan-India panel survey designed and implemented by the University of Maryland, College Park, USA, and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi, India. The third wave of IHDS interviewed 47,842 households between April 2022 and June 2024 using Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI). A distinctive feature of this wave was the effort to track and interview IHDS sample members from previous waves who had moved out to other places for reasons such as marriage, work, studies, etc. Interviewers were tasked with obtaining migrants’ contact information and to make a call to those numbers whilst they were still present at the root household, notifying them that they can expect a call in the next few weeks for a telephone survey. Interviewers recorded information on who the number belongs to in the CAPI instrument.

A total of 46,147 migrants with phone numbers were identified by the above tracking process (not all root households had a migrant). An external telephone survey agency was contracted to interview 40,535 (88%) of these cases while the remaining 5,612 cases (12%) were completed by internal IHDS staff. Interviews were conducted using Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) in eight different languages, with all interviewers undergoing a structured training program. Interviewers made up to ten contact attempts. The CATI instrument was a shorter version of the CAPI instrument and comprised questions relating to household composition, education and work activities of members, assets owned, etc. The median interview length was 28 minutes.

Our focus is on female married-out migrants, who comprise half of the migrant sample (23,353 cases). CATI interviewers were trained to prioritize contact with the married female migrant, even when the phone number provided by the root household belonged to the gatekeeper (i.e., someone other than the migrant).

C. Gatekeeping in the IHDS survey

As shown in Figure 1, gatekeeping for the IHDS migrant survey arises in two stages.

The first hurdle comes at the CAPI stage when the root household does not share the migrant’s telephone number but rather that of the gatekeeper (Box 1). This gatekeeping propagates through the process when the CATI interviewer attempts the telephone number and the gatekeeper either refuses to cooperate (Box 2) or insists on a proxy interview (Box 3). Even if the root household provided the migrant’s number, the call might be picked up by another member of the migrant’s household, or there may be implicit pressure to hand the call to another (likely male) person (Box 5).

D. Prevalence of gatekeeping

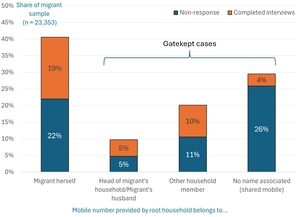

A total of 109,681 calls were made to the married-out female migrant sample. Figure 2 shows that only 41% of the primary contact numbers belonged to the migrants themselves. The other categories are those of gatekept cases since other persons must be first spoken to in order to get to the migrant. This results in a baseline gatekeeping estimate of 59%.

A significant share (30%) of phone ownership seen in Figure 2 is that of ‘no name associated’ which, given the discussion in Section A, is likely to be that of shared mobile numbers. In this light, the 59% gatekeeping prevalence can be an overestimate since there is some likelihood that the female migrant will pick up the call herself. If we take the estimate of female pick-ups of shared numbers as 33% (based on estimates by Hersh et al. [2021] reported in Section A), then we arrive at a gatekeeping prevalence estimate of approximately 50% (100% – (41% + 33%*30%)).

The overall non-response rate for the survey is 63% (sum of the blue bars in Figure 1; AAPOR RR1 definition). But when a shared mobile number is provided, the non-response rate is 88% compared to the 54% non-response rate when the phone number belongs to the migrant herself. A counter-intuitive result is that the lowest non-response rate (48%) is when the mobile number provided is that of the household head or husband.

E. Case dispositions

Distributions of case outcomes (rows in Table 1) differ for the different gatekept categories (columns in Table 1); an overall test yields a test statistic of 3915 with 44 degrees of freedom which is significant at a 0.1 level.

First, we find that even when calls were made to the migrant’s phone number, 15% of the cases involved a gatekeeper (sum of 2.b, 3.b, 4.b, and B.b in the first column of Table 1). These gatekeeping episodes add another 6% to the nominal gatekeeping prevalence estimate, taking it to 65% or 56% (depending on how shared numbers are handled).

Second, non-contacts account for a large component of outcomes and is approximately double for the shared mobile category (49%) compared to the other categories (25%, on average). Third, refusals are a minor component of non-response (10% overall) and do not vary by mobile ownership categories. Fourth, cases involving blocking/avoiding call-backs including those with an agreed appointment (A.3 and A.4 in Table 1) or cutting the call in the middle of the interaction (A.5. in Table 1) account for 17% on average for each of the first three contact person categories in Table 1, but this increases to 27% in the case of a shared mobile number, with gatekeepers almost fully contributing to the difference (e.g., A.3.b in Table 1 is only 3% for the 1st three categories but 7% for the shared mobile category).

Finally, the benefit of a non-gatekept contact attempt is that, conditional on obtaining cooperation, the probability of a proxy interview is relatively low at 17% (8%/46%) compared to approximately 45% when the head of the household/husband or another household member is the gatekeeper. Surprisingly, the probability of a proxy interview for the shared mobile category is only 25%. We explore factors associated with proxy interviews in the next section.

F. Factors associated with gatekept interviews

We analyze the likely determinants of a proxy interview (conditional on cooperation; ‘B’ in Table 1 comprising 8,594 cases) by fitting the following model where the outcome variable is a Bernoulli variable, set equal to one for a proxy interview and zero otherwise. Respondents are clustered within interviewers and states but an interviewer interviews respondents across states, thereby giving rise to a cross-classified structure. Our model is:

\[\begin{aligned} \log\left( \frac{p_{ijk}}{1 - p_{ijk}} \right) &= \ \beta_{0} + u_{0j} + u_{0k} + \mathbf{R}_{ijk}\pmb{\beta}_{R} + \ \mathbf{Z}_{j}\pmb{\beta}_{Z};\\ u_{0j} &\sim\ N\left( 0,\ \sigma_{iwer}^{2} \right);\\ u_{0k} &\sim\ N\left( 0,\ \sigma_{state}^{2} \right) \end{aligned}\]

We include state random effects to adjust for region-specific differences in proxy reporting that would otherwise be misattributed to interviewers (in the absence of random interview assignments) when we estimate Our data have 2,476 proxy interviews out of 8,594 completed interviews (29%). The vector R comprises the following variable values: the root household heads caste (General category [reference category] 24%, Other Backward Caste 42%, and Scheduled Caste/Tribe 34%) and religion (Hindu [reference category] 82%, Muslim 13%, and Other 5%), and the migrant’s location (Rural 73% and Urban [reference category] 27%), age (mean: 28.5 years, range: 18–45 years), and number of years of education (mean: 10 years, range: 0–17 years). We also include the time lag between the CAPI and CATI interviews (mean: 286 days; range: 205–500 days), hypothesizing that a greater lag will lead to an increased chance of a proxy interview.

The vector comprises values on variables collected from interviewers (except for ‘interviewer workload,’ which was computed): sex (43 female [reference category] interviewers and 13 male interviewers), age (mean: 31 years; range: 25–50 years), marital status (28 currently married [reference category] interviewers and 28 unmarried interviewers, i.e., those who were divorced, widowed, or never married), survey experience (mean: 2.7 years; range: 0–12 years), and workload (including non-married female migrant cases; mean: 845 interviews; range: 153–2101 interviews).

We fit models with and without to estimate the proportion of explained by Table 2 displays the odds-ratios for the model terms.

Given the discussion in Section E, it is unsurprising that the initial contact person is the biggest predictor of a proxy interview. The caste and religion of the root household’s head (very likely to be the same for the migrant given that most marriages in India are endogamous) are influential in determining gatekeeping, e.g., Muslim migrant households are estimated to have a 21% greater odds of completing a proxy interview compared to Hindu households. Older and more educated persons are associated with lesser gatekeeping. On average, compared to a 28.5-year-old migrant (the mean migrant age), a 33.8-year-old migrant (1 standard deviation higher than the mean) has a 12% lower odds of a proxy interview, and compared to someone who has approximately 10 years of education, a migrant with 15 years of education has a 23% lower odds of being gatekept.

In addition to the fixed effects, we have and (these estimates were based on a model that did not include yielding an estimated intra-interviewer correlation (IIC) for the proxy interviewing outcome = where is the respondent-level logistic distribution variance (Snijders and Bosker 1999, p.224). The IIC represents how correlated two random interviews from an interviewer’s workload are with respect to their being proxy interviews. The estimated IIC of 0.15 is unsurprising in the LMIC context, e.g., Walcott, Cohen, and Ferris (2024) estimate an average IIC of approximately 0.2 for financial recall questions in a phone survey in Uganda.

Table 2 shows that some interviewer-level variables have a strong association with the occurrence of proxy reporting. The odds of eliciting a proxy interview are 83% higher for male interviewers compared to female interviewers. Intriguingly, even after adjusting for age, unmarried interviewers are associated with 47% lower odds of gatekeeping compared to currently married interviewers. Finally, the interviewer questionnaire asked whether the interviewer prefers interviewing male or female respondents. Interviewers who prefer interviewing male respondents have a 91% higher odds of obtaining a proxy interview compared to those interviewers who prefer interviewing female respondents. Together, the interviewer variables explain 28% of the between-interviewer variance of the outcome.

G. Discussion

The IHDS migrant telephone survey does not contain sensitive questions. Also, pre-notification calls were made to the provided numbers, specifically asking to speak with the migrant. Despite this, gatekeeping was between 56% and 65%, an unignorable prevalence estimate. Of course, the time lag between the CAPI and CATI interviews (due to operational reasons), might have made pre-notifications much less effective in this case. A closer look at the case outcomes provides a nuanced view of gatekeeping and tells us that not all gatekeeping behaviors are alike. When the gatekeeper is a husband or head of the household, making contact is easier and the non-response rate is six percentage points lower than if we could contact the migrant directly. However, the chances of a proxy interview then go up dramatically (43% versus 17% for a non-gatekept interview). All considered, it is important to make efforts to contact the selected female respondent directly.

The shared-mobile number category poses a special challenge where the operational focus should be on coming up with methods to establish contact with the selected respondent; once that is done, the proxy interviewing rate for that category is at a relatively low 25%. In this category, we also see an enhanced risk of contact persons cutting the call (#5 in Table 1) and blocking/not answering further calls (#3.b in Table 1). Analysis on the optimum time to call such numbers will be useful.

While not a gatekeeping-specific insight, we note that refusals were a small proportion of the outcomes. However, in 21% of all cases, some contact was made but it neither resulted in a refusal nor an interview (sum of A.3, A.4, and A.5 in Table 1). This hints at ‘soft refusals’ where cultural norms do not encourage an outright refusal but there is an avoidance to be interviewed. In preliminary analyses of interviewer observations, we found that contact persons are often unclear about why the survey is being done and how the data will be used. Interviewers should be trained to get a ‘foot in the door’ and have an elevator pitch ready for these cases.

The interviewer variable with the largest impact on proxy interviewing is the preference to interview males. This points to a potential mechanism where interviewers may not be maximizing efforts to overcome gatekeeping. This is another area to be addressed in interviewer training. Apart from this variable, interviewer demographics are more important than experience or workload in determining the occurrence of a proxy interview. It is essential to have diversity in interviewer profiles and, based on the theory of liking (Bittmann 2020; Groves, Cialdini, and Couper 1992), possibly matching sample cases to interviewers, e.g., assigning female interviewers to contact female sample persons.

While we have dealt with gatekeeping in the Indian context, its learnings are applicable in a broader context since many LMIC countries share a similar operating landscape. For example, in their study of 36 LMIC countries, Elkasabi and Khan (2023) show that the high penetration of household mobile telephony can be a misleading indicator of coverage since a sizable proportion of adults are accessible only via the household’s phone owner (gatekeepers). Our focus on the gatekeeping of female members also resonates with the larger theme of male-oriented decision-making in households, especially in LMICs (Horowitz and Fetterolf 2020).

Future research can analyze whether there are regional variations in gatekeeping prevalences and if survey responses differ between proxy interviews and interviews with the selected respondent. The finding that interviewers’ marital status impacts gatekeeping is a prompt for more research on uncovering mechanisms governing gatekeeping. The results seen in this paper could be different for face-to-face surveys; the physical presence of the interviewer may translate to better communication of the survey request leading to lower gatekeeping rates, but this hypothesis needs to be tested. Similarly, it also remains to be seen whether panels surveys are subject to lesser gatekeeping in LMICs (this was IHDS’ first phone survey with migrated-out sample members) due to greater rapport being built with the respondent over waves.

Lead author contact information

Sharan Sharma

3133, Parren Mitchell Art-Sociology Building, 3834 Campus Dr., College Park, MD 20742.

snsharma@umd.edu