Introduction

United States Postal Service (USPS) delivery delays have been reported in recent years (Pettypiece 2024; Heckman 2024) and proposed changes at the USPS may result in additional delays (Higham 2025; USPS n.d.). Extended delivery times and delays can create challenges for data collectors. For example, slower delivery can increase the field period and raises the possibility that the distribution of follow-up materials overlaps with completed mail booklets that are still en route. An approach to limit this circumstance is to purchase tracking information on inbound courtesy or business reply envelopes (BREs) so that data collectors can monitor when the USPS collects each recipient’s BRE. We incorporated inbound BRE tracking for a 2024 survey to evaluate its efficacy and potential cost savings.

This article is structured as follows: first, we discuss what inbound mail tracking is and its potential benefits to survey data collectors. Second, we provide an overview of our data and methods. Third, we use crosstabulations and descriptive statistics to evaluate the utility of inbound mail tracking. Finally, we discuss our findings and their implications for survey research.

What is Inbound Mail Tracking?

Individuals who send bulk mail regularly track and monitor when the USPS delivers the mailed materials to their intended recipients. Similar to tracking outbound mail delivery, inbound mail can be setup so that data collectors know when the materials are en route back to them. Implementing inbound tracking requires printing an Intelligent Mail barcode (IMb) on each BRE. IMbs are a 65-bar barcode used by the USPS to sort and track mail (USPS n.d., 2022b). Several pieces of information such as service type and mailer identifiers, the serial number, and routing code are contained in the 65-bar IMbs that allow users to track mail (USPS 2022a). IMbs are either serialized or non-serialized. Serialized IMbs allow users to track individual pieces of mail because of unique serial codes applied to each envelope, while non-serialized IMbs are used to track large batches of mail without unique serial codes for individual envelopes. Because of the properties of serialized IMbs, their usage increased during the 2020 election, as many states used IMbs on vote-by-mail ballot envelopes. For example, California’s Governor issued an Executive Order that all county election officials were required to use IMbs on vote-by-mail ballot envelopes (Lean 2020). However, inbound mail tracking has broader applications that may benefit survey researchers. For instance, we explored whether this data could provide early insights into survey response returns, allowing us to suppress follow-up mailings for individuals who had already put their questionnaires in the mail.

Costs and Benefits of Inbound Mail Tracking

Survey research centers and/or their print/mail partners with a USPS Mailer ID and Customer Registration ID (CRID) can establish an account with an authorized USPS vendor that is capable of providing mail tracking data (e.g., Snailworks, Track and Trace, Track My Mail, and Greyhair) for a fee. Vendors generally charge a setup and per-piece cost that currently ranges from $0.003 to $0.02 depending on volume. The vendors generate a unique serial ID that is appended to the end of each BRE’s IMb to collect data from USPS tracking feeds. In addition to the actual tracking fees, printing and labor costs may also be affected as the process requires a custom BRE with the IMb for each recipient and matching the BRE to the corresponding survey materials.

While using inbound tracking adds costs, the benefits may justify the expense in certain scenarios. First, IMbs provide insights on mail returns. At each stop from collection to delivery, the USPS scans the IMbs on BREs and creates a continuously updated list documenting the date of the initial, most recent, and delivery scans. Using this list, researchers can track the proportion of the sample that received and sent back a mail questionnaire. This information may help researchers make decisions regarding timing of reminders, staffing, and response rate projections (Dillman, Smyth, and Christian 2014). This is directly related to the second benefit of IMbs, their cost-saving potential. By using inbound mail tracking, researchers can suppress sending follow-up materials to respondents who have completed their mail booklet even if it has not been delivered to the data collectors for processing, thereby reducing printing/postage costs for subsequent mailings. Further, reducing outreach to respondents who have already dropped their completed survey in the mail may improve their overall experience by preventing unnecessary reminder contacts after survey submission.

The potential benefits for using inbound tracking are clear, but it is less clear that it is a useful tool for survey researchers. The utility of this tool relies on timely and accurate information being provided by the USPS. However, the USPS, like all organizations, is subject to human and technological errors. For example, BREs may not be scanned after pickup or delivery or may be scanned but not in time for survey researchers to make important mailing decisions (e.g., suppression of cases or timing of reminders). For these reasons, we evaluate the accuracy of the USPS inbound tracking data by examining both the number of days prior to receipt of the physical survey packet that we were alerted that the recipient had placed their BRE in the mail and the accuracy of the tracking information.

Data and Methods

Our survey population was Iowa adults who receive health insurance through a state program. To participate in the program individuals must meet the following requirements: aged 19-64, have an income that does not exceed 133% of the Federal Poverty Level, live in Iowa, be a U.S. citizen, and not otherwise eligible for Medicaid. Data collection was sequential mixed-mode (Push-to-Web (PTW) followed by a paper survey booklet) with four mailings. The initial two mailings included visible cash (Debell et al. 2020; DeBell 2023) in a large window on the front of the envelope (Bilgen et al. 2024). All letters invited recipients to complete the survey online using the provided URL or QR code, which can improve participation and representativeness (Endres et al. 2024; Endres, Heiden, and Park 2024; Marlar and Schreiner 2024).

A total of 17,000 individuals were randomly selected from the state’s health insurance database to receive survey invitations. The total was reduced to 16,855 when individuals who were flagged as having moved out of state in the National Change of Address database were removed from the sample. It is also worth noting that this population is more mobile than a general population sample with more than 2,000 letters returned as undeliverable. Ultimately, 2,066 individuals completed the survey and an additional 135 provided a partial response for an American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) response rate 2 of 13% (AAPOR 2023). Table 1 details the mailing timeline and contents while Appendix A includes a breakdown of sample disposition codes.

Data Collection Timeline

We incorporated unique IMbs on each BRE (mailings 2 and 4) using SnailWorks. The cost was $1372.90 per mailing ($2,745.80 total) inclusive of vendor fees and additional printing/labor costs. Recall, we were interested in evaluating the number of days between USPS collecting the completed paper survey and our receipt of the completed paper survey, inbound tracking accuracy, and potential cost savings. While cost savings were not possible from the final mailing, we nonetheless incorporated IMbs on this mailing to have additional information regarding accuracy. Using inbound tracking, we monitored BREs en route to us to suppress follow-up mailings for these respondents. Inbound tracking documented when each BRE was first scanned, most recently scanned, and ultimately delivered to our university’s mailroom. We used this information to determine the days between USPS collection and delivery.

Results

We used the inbound tracking records to supplement our list of completions (web and already delivered/processed paper survey booklets) to suppress follow-up mailings. Table 2 displays the crosstabulation of inbound BREs scanned by the USPS prior to mailings 3 and 4 and those received by the center early enough to be suppressed for the subsequent mailing. An additional suppression was defined as any respondent that had their BRE scanned by the USPS indicating that it was on its way back to our center but had not been delivered (Table 2, Column 2). In total, we suppressed an additional 90 addresses from the third mailing and one additional address from the fourth mailing based on the inbound tracking information that indicated the survey booklet was in possession of USPS and en route back to us. Note that we compared the total cost saved to the cost of implementing inbound tracking for the second mailing (i.e., $1,372.90) because there were no mailings after the fourth mailing and thus no potential savings. We saved $163.80, resulting in a net loss of $1,209.10. The amount saved offset the direct vendor fees, but not the added printing/labor costs.

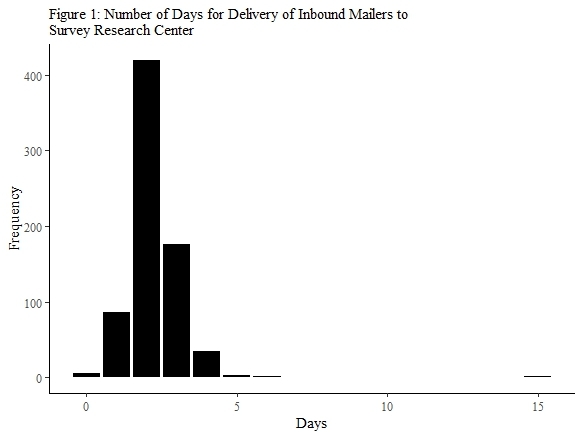

Table 3 reports the return rate of paper survey booklets. Three (of 727; 0.41%) BREs scanned as delivered by the USPS were not received prior to data collection concluding, while 9 BREs were scanned, at least once, but were not scanned as delivered. Ten BREs were never scanned by the USPS but were received by the center. Figure 1 displays the number of days it took for our survey center to receive BREs. Most were received within 1 week from the first USPS scan. The modal delivery window was 2 days. The median time of receipt was 3.5 days.

Lastly, it is important to note the types of tracking errors identified (Table 4). The first type of potential error is for BREs that were never scanned by USPS and not received by our survey center; this type of error is not observable. The second type of error is for BREs that were never scanned by USPS but were delivered to our center (n=10, 1.3%). The third type of potential error is for BREs that were not scanned as delivered by USPS (but were scanned en route) and were not received by our center, which did not occur for this project. The fourth type of potential error is for BREs that were scanned en route but were not scanned as delivered but were received by the center (n=9, 1.2%). The fifth type of error is related to BREs that were scanned as delivered but were not received by our survey center. This scenario occurred three times (0.4%); however, it is unknown if the BREs were never delivered to campus or were lost in transition from the university’s mailroom to our center.

Conclusion

In summary, inbound tracking did not provide enough additional suppressions to offset the added costs for this project. However, the study design likely contributed to the minimal cost savings (66% of respondents participated online). A single-mode mail survey or even a mixed-mode design that begins with paper booklets might yield cost savings that fully offset the inbound tracking costs. Greater cost savings would also be expected if the window between mailings was smaller and/or for a national (or multi-state) study which should take longer to move from the respondent to the data collectors than in this Iowa-only study. Thus, we suggest continued evaluation of inbound tracking in varied designs, contexts, and as postage rates and delivery times continue to evolve.

While the feasibility of inbound mail tracking depends on factors like mailing size, package type, and response volumes, its value is not solely measured in dollars. For organizations managing large-scale mailings, knowing which recipients have mailed back their surveys three (or more) days before receipt can be a powerful tool for improving efficiency, reducing waste, and perhaps even enhancing respondent satisfaction.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statements

The University of Northern Iowa Institutional Review Board determined that the project did not meet the regulatory definition of human subject’s research since it is an evaluation of a Medicaid demonstration project.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Corresponding author contact information

Kyle Endres, Center for Social & Behavioral Research, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, IA 50614, USA; E-mail: kyle.endres@uni.edu