As the communication behavior of survey respondents evolves, so too must the methods used to trace them. Traditional approaches to respondent tracing have long relied on physical mailing addresses and phone numbers, methods of contact that are declining in relevance now that fewer than half of younger adults check their “snail mail” daily and over 80% of Americans report that they will not answer calls from unknown numbers (McClain 2020; USPS 2018). The vast majority of Americans across all age groups do use some form of social media (Gottfried 2024), however, making social media a potentially powerful tool for tracing and communicating with survey respondents (e.g., Bennetts et al. 2021; Rhodes and Marks 2011; Schneider, Burke-Garcia, and Thomas 2015). Mailing addresses and mobile numbers may change hands if respondents move homes or switch wireless carriers, but profiles on platforms including Facebook and LinkedIn are required to be registered under the account holder’s legal name, offering unique advantages in continuity of contact information over time. Even in cases of legal name changes or where a nickname is used on a profile, a user’s registered legal name is often still retained as a search term.

Despite the potential value of social media for respondent tracing, however, identifying survey respondents on social media platforms can be challenging (e.g., Daniel, Brooks, and Waterbor 2011). LinkedIn and Facebook deliberately safeguard against bulk or automated searches, and scraping public data from LinkedIn has been a subject of ongoing litigation in recent years (Berzon 2022). Email addresses attached to social media profiles are frequently private, and public records search engines often do not extend to social media. Platforms such as LexisNexis Social Media Locator advertise the ability to locate social media footprints using “deep web” searches, but the deep web includes information such as database content that is commonly understood to be private, and such searches therefore may be less clearly ethical in the context of human subjects research than in corporate or legal applications.

In this study we report on a protocol for searching and identifying respondent social media accounts that relies strictly on public information available through standard search engines (the “surface web”). Using a random subsample of the respondent population for a survey in development (N=450), our objective was to establish an efficient and replicable approach to 1) locating possible social media accounts on the three most commonly used platforms in our respondent demographic (LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram), and 2) determining the likelihood of a match between a social media account and a given survey respondent. We describe the development of our protocol, report the percentage of our sample for which we were able to locate social media accounts, and share insights for other researchers seeking to trace respondents on social media.

DATA AND METHODS

The strategy described here is intended for researchers with a defined sample that they are seeking to trace. This is standard in later waves of longitudinal surveys, such as Bennetts et al.'s (2021) report of using Facebook to trace participants for a five-year follow up of a randomized control trial. It is also common in cases where a new sample is defined by shared institutional or program involvement, such as Daniel, Brooks, and Waterbor’s (2011) report of using Facebook to trace graduates of federally funded medical training programs. The applied example in this study falls into the second category, wherein respondent names are drawn from institutional records but current contact information is not available.

Our sample was randomly selected from the New York University World Trade Center Health and Wellbeing Study (NYU-WTC), a survey in development in which the respondent population includes all alumni who resided in NYU undergraduate dormitories during the Fall 2001 semester. After approval by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board, we obtained institutional data on this population from NYU, including student names, dates of attendance, field(s) of study in Fall 2001, final degree level pursued at NYU, and calendar year of degree, if conferred. We did not receive data on respondent race, ethnicity, birth year, or sex or gender, but most respondents will have been born between 1979 and 1984, and 55% of our random subsample was coded by our team as having an identifiably female given name. As this sample consists of individuals who were admitted to a selective university where the graduation rate is high (>80%), educational attainment in this cohort is expected to be above the national average.

Search protocol development

The research team consisted of one faculty member, two graduate students, and six undergraduates at a large research university. All team members had prior experience with searching for individuals on social media outside of formal research contexts, and our objective was to build on this experience to develop a standardized search protocol that was systematic, replicable, efficient, and relied strictly on publicly accessible data.

-

Iteration 1. Each team member was assigned a list of 25 individuals randomly selected from our full sample and asked to search for social media accounts for these individuals online. Searches could be conducted via standard search engines (e.g., Google), public records search platforms, or directly on the three most popular profile-based social media platforms among college-educated Americans: Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram (Gottfried 2024). Each team member documented and revised the steps in their search process for effectiveness and efficiency and noted whether they found a match, a possible match, or no match for each respondent.

-

Iteration 2. The protocols that we had individually developed converged on quite similar search strategies. We reviewed our approaches and agreed on a shared protocol, which we each tested on additional random subsamples of 25 respondents to generate our final protocol. We applied our final protocol in an additional search round for any respondents not located on social media in iteration 1.

RESULTS

Search protocol

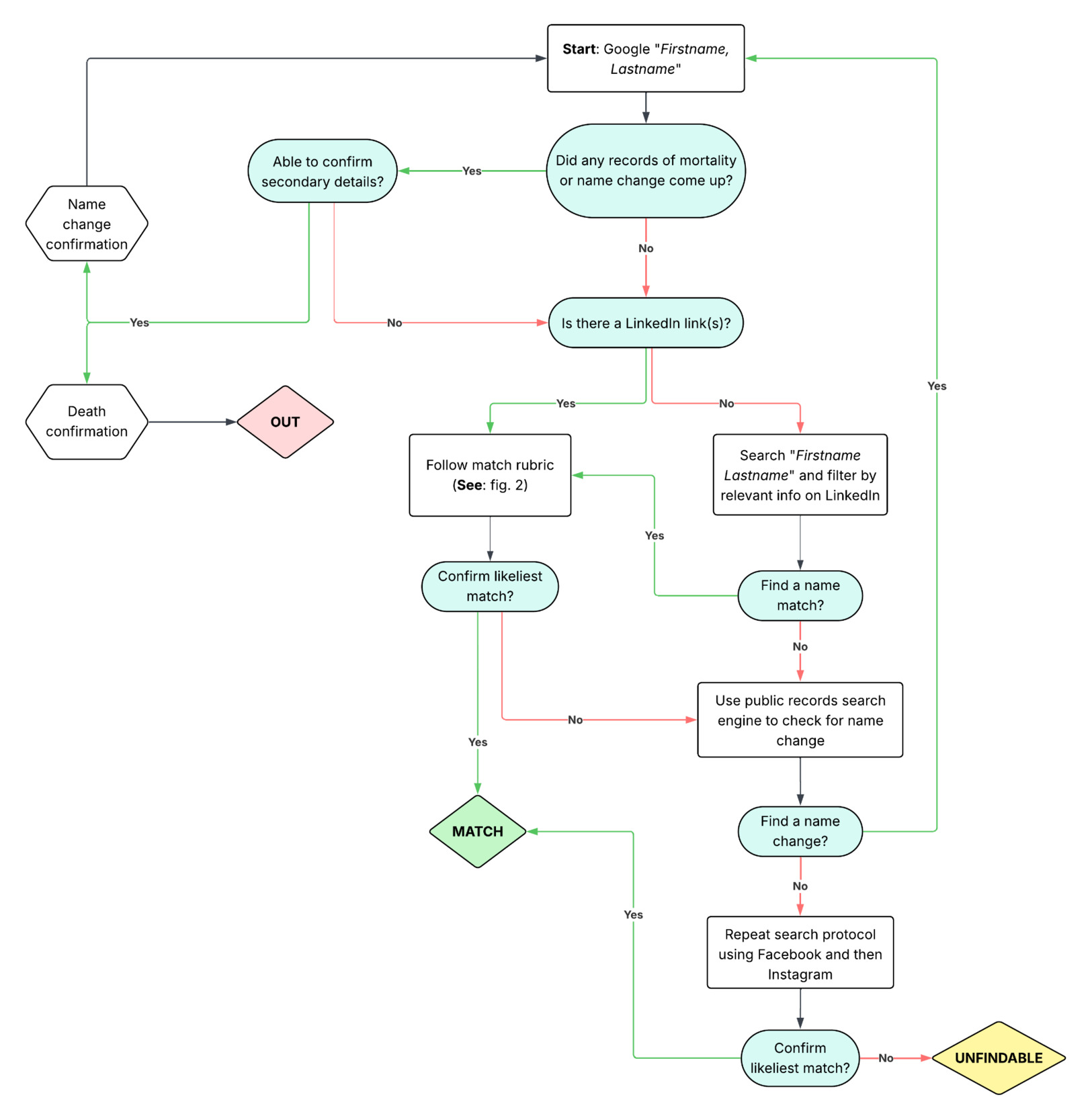

Our finalized search protocol is detailed in Figure 1. Key steps included:

-

Google search. Our first step was a web search for respondents’ full names, plus secondary search terms (“NYU” or “New York University” in our case) when names were common. Social media profiles were often the first link returned. Search engines such as Google can return social media accounts that will not be returned in searches directly on a given social media platform if a profile is no longer in regular use, but such profiles may still have linked email addresses for messaging purposes. An initial Google search may also quickly return information suggesting a name change or evidence that the respondent is deceased. If a given search returned no social media accounts but did return other information that was a definite match (e.g., a website), our team explored the available resources for connections to social media and/or contextual clues that could be used to identify the individual on social media.

-

Social media search. Of the three social media platforms used in our search, there was variation in the likelihood that a respondent would be located and confirmed based on the amount of information that is publicly available on the platform with which to verify name matches. Because work and education histories are publicly available on LinkedIn profiles, LinkedIn accounts allowed us to quickly verify name matches by confirming university enrollment and enrollment dates. Facebook was the next most likely platform to have sufficient public secondary data to confirm a name match. Unlike Facebook and LinkedIn, Instagram does not require legal name validation and had the least publicly available data to confirm name matches.

Because our survey population is both demographically likely to be on LinkedIn and LinkedIn offered the most information to confirm matches, if an initial Google search did not return a social media profile, we next went to LinkedIn directly to search for accounts on that platform. If we did not find a profile on LinkedIn using our protocol, we moved on to searching for Facebook accounts, and finally for Instagram accounts, with each round of searches repeating the same basic steps. For our purposes, respondents were counted as having been found on social media if they had at least one confirmed social media account. -

Name change check. When no name match was found via a Google search or searches on the three social media platforms, we turned to public records search platforms for evidence of a possible name change. As we deliberately avoided in-depth public records searches due to concerns over respondent privacy, a number of basic public records search platforms were successful at helping us identify name changes that led to a confirmed identity match on social media based only on respondent age and history of having resided in New York. Examples included fastbackgroundcheck.com or fastpeoplesearch.com, but there are many similar options in this field.

Match definitions

For each name match found using the protocol in Figure 1, we attempted to confirm the respondent’s identity using available secondary details (Figure 2). In longitudinal surveys, secondary details will generally be available from an initial survey wave, such as in Bennetts et al.’s (2021) description of using birthdays and Facebook connections to respondents’ known family members as confirmatory information. In cases where respondent names are drawn from institutional records, secondary details can either be drawn from those records or from information about the institution itself, such as in Daniel, Brooks, and Waterbor’s (2011) report of using residential location and student or alumni status as confirmatory information. In our case, secondary details included NYU enrollment in Fall of 2001, an age that roughly aligned with undergraduate enrollment in Fall 2001, and undergraduate major.

We sought to both confirm these secondary details in connection with a name match and to ensure that there were no conflicts between these secondary details and a name match. In cases where multiple names matched, the steps detailed in Figure 2 were followed for each match. In theory, this could result in multiple profiles in the “possible match” category, although in practice we encountered no cases in which there were multiple “possible match” candidates.

Names of respondents that were not found on social media using our search protocol were transferred to a master sheet for a second-round search by a different member of the research team. If respondents could not be found after independent searches by two team members, the respondent was deemed unfindable.

Success rates

We were able to confirm social media accounts for 70% of our sample (315/450), a figure that roughly aligns with national estimates of social media usage in our sample demographic on the three platforms considered (Gottfried 2024). Most searches were completed within five minutes and often faster. After two search rounds, approximately 5% of our sample was not found on social media but had other contact information readily available online (e.g., personal or business websites), and another 11% was findable in public records searches but not elsewhere. Additional search rounds returned plausibly current contact information for nearly 99% of our sample, but the percentage found on social media remained at approximately 70%. Key factors associated with lower likelihood of finding a respondent on social media included:

-

Common names. Of the 30% of respondents who were not found on social media, one-third had “common names,” defined as surnames that appeared more than five times in our full sample.

-

Occupation. Unsurprisingly, respondents who were in occupational positions with the potential to garner unwanted contact, such as medical doctors, were far less likely to be found by our team on social media. Respondents in the arts were also generally less likely to be found on social media, and when they were found, it was less frequently on the business-oriented LinkedIn.

-

Name changes. Although most women in the U.S. take their spouse’s surname after marriage, name changes are becoming less common over time and are less common among higher educated women (Lin 2023). Of the respondents that we were able to locate, we found name changes for only about 20% of those with identifiably female given names, presumably reflecting a demographic less likely to change their surnames after marriage plus an unobserved percentage of our sample that is unmarried. Name changes among women increased search time, but consistent with women being more likely than men to use Facebook and Instagram (Gottfried 2024), identifiably female given names made up a minority (44%) of respondents who were not found on social media (55% of our sample had identifiably female names).

DISCUSSION

Social media remains an underutilized tool for survey researchers seeking to trace respondents. Although some public records search platforms are now able to return potential social media account matches, major social media platforms such as Facebook and LinkedIn deliberately safeguard against bulk or automated searches, and searches that utilize data from the deep web beg questions about the ethics of respondent privacy and consent in the digital age. In this study, we developed a search protocol to standardize and streamline the process of locating respondent accounts on the three most popular social media platforms in our survey demographic (LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram) using only publicly available information, along with a match definition rubric for deciding whether a respondent was correctly matched to a given social media account.

The approach that we developed is specific to our test sample of highly educated older millennials but can be adapted to other respondent populations as well. Key steps for adapting our methodology to other samples would include ascertaining which social media platforms are most popular in a given survey demographic and generating a list of secondary details that can help confirm respondent identity after a name match (e.g., Bennetts et al. 2021). We anticipate variation in the effectiveness of our protocol by factors such as age and SES, as LinkedIn, by far the easiest platform on which to confirm respondent identities, is more commonly used by college-educated respondents. Younger demographics are more likely to use platforms such as Snapchat and TikTok on which verifying respondent identity would be far more challenging—but 68% of Americans across all demographics report using Facebook (Gottfried 2024), and the demographics of social media use are more generally fluid and expected to change as platforms evolve and cohorts age. Some steps in our process could plausibly be automated, but scraping public data from social media platforms has been the subject of litigation in recent years (Berzon 2022), many leading AI platforms have privacy protections against searching for individual profiles or contact information, and an automated process would likely still require some form of direct match vetting similar to our protocol.

We emphasize that this study did not extend to contacting respondents through social media. Prior research has reported varying rates of respondent engagement following social media contact (Bolanos et al. 2012; Daniel, Brooks, and Waterbor 2011; Mychasiuk and Benzies 2012; Nwadiuko et al. 2011; Rhodes and Marks 2011; Schneider, Burke-Garcia, and Thomas 2015), and although rates of social media use in the U.S. are high, they are lower than rates of other forms of communication such as cell phone use, which is now nearly universal (Pew Research Center 2024). We thus suggest that future research should explore the utility of social media within a multi-pronged respondent tracing strategy, including other electronic text-based approaches, such as text messaging and email.

Corresponding author contact information

Amelia R. Branigan, University of Maryland Department of Sociology, 2112 Parren Mitchell Art-Sociology Building, 3834 Campus Dr, College Park, MD 20742

branigan@umd.edu