Introduction

The number of people accessing the web by mobile devices is rapidly increasing. Unfortunately, conducting representative research using only smartphones is not possible, because the penetration of smartphone users is too low and selective (Fuchs and Busse 2009; PewInternet 2013). One solution is to provide smartphones to the people who do not own one.

The Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP and CentERdata (Tilburg University) jointly tested a time-use app on smartphones with 100 participants, both experienced and inexperienced smartphone users. Those without a smartphone could borrow one and could get extra instructions in using the phone and the app. This paper gives an overview of these tests and addresses the question whether smartphones and apps are feasible to conduct survey research with inexperienced (and experienced) users.

Study Design

The app design and the feasibility of completing time use surveys using a smartphone were evaluated in a series of tests. The time-use app was designed for the Android operating system of smartphones[1] and tested under a sample of 100 subjects from an online access panel. Initially, 50 panel members who owned an Android smartphone were selected, and 50 panel members without a smartphone who were able to temporarily borrow an Android-phone provided by CentERdata. Both groups had comparable distributions of the background variables age, gender, and education (see Table 1). Although they were not representative of the general public, this was not considered necessary as the main aims of the tests were experimental and explorative.

The participants received an introductory letter about the study and a written manual on how the app works. In addition to the written manual, participants could watch an introductory film on YouTube explaining how to use the app (and how to use the smartphone for those who had borrowed one). In addition, during the fieldwork period a helpdesk was available to answer (technical) queries. People participating with their own smartphone could download the app via a link on the CentERdata website. (Details were included in the invitation letter.) For participants with a borrowed phone, the app was already installed.

Developing the App

The design of the app was as similar as possible to the way in which the regular time use data are collected by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP and Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Thus, following the Harmonized European Time Use Surveys (HETUS) guidelines (Eurostat 2009), the time-use app consisted of a diary in which participants could fill in their time use (see Figure 1), which consist of a main activity, sideactivity and with whom the participant was in the same room. Respondents were asked to complete the time-use app during 2 days, one weekday and one weekend day. Each day started at 4:00 a.m., and respondents had to complete 24 hours in 10-minute time slots. Respondents could complete the remaining time intervals of the 24-hour period until noon the next day. After the tests, an evaluation questionnaire was sent to the participants, and ten qualitative in-depth interviews were held to learn more about the experiences and difficulties in using the app.

Comparison Between Experienced and Inexperienced Users

In order to evaluate whether both groups are able to meaningfully participate in a smartphone time-use survey, we compare on overall response, data quality, number of records, and self-reported evaluation of the tests. Table 2 shows the responses for both user groups. It is interesting to note the low number of completes for inexperienced users on the first fieldwork day. After this first day, all the participants who did not have a complete day received a reminder call, which helped in boosting the number of completes for the second day. Overall, it can be seen that not all respondents recorded time data for the entire day.

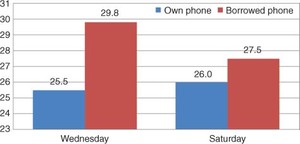

A first way of checking data quality is to count how many different episodes people report (Kamphuis et al. 2009; United Nations 2005). An episode is defined as a continuous time period in which a respondent does the same activity (and side-activity) with the same person(s) or alone (e.g., “partner leaves room while watching TV” is a new episode). The general assumption is that the more episodes people report, the higher the data quality will be (in terms of greater accuracy of the reported time-use data). Figure 2 presents the differences in the number of episodes recorded by respondents participating with a borrowed smartphone or their own device. In particular, it can be seen that the number of episodes is somewhat higher among respondents with a borrowed phone compared with respondents using their own phone. It might be the case that persons with a borrowed telephone feel more obliged to do a good job using the time-use app, and therefore complete their diary more accurately (i.e., by recording more episodes) than participants with their own smartphone.

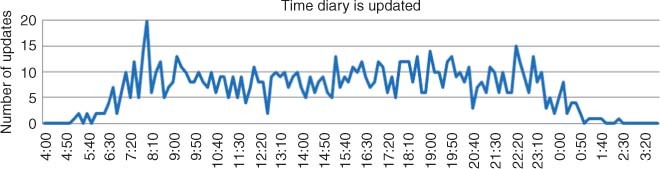

A second indication of data quality is the number of times that the smartphone diary was updated during the day. The general idea is the more updates, the higher the data quality because there is less recall between doing an actual activity and recording this in the smartphone diary. Figure 3 shows the time points at which respondents recorded activities in their diary app. As might be expected, most respondents fill in their diary at times when they are most likely to be awake, i.e., between approximately 6:00 a.m. and 1:00 a.m. The peak moment for recording activities in the diary is at 8:00 a.m., which corresponds to the moment when the first reminder of the day is sent to respondents, reminding them to fill in their diary. On average, people fill in their diary 11 times a day, with 207 minutes (roughly three and a half hours) between the updates. A slight difference can be observed in how often participants with and without their own smartphone recorded activities in the diary: smartphone owners recorded their time use about ten times a day, while people with a borrowed smartphone did so on average 12.5 times a day. This may be related to the above observation that those with a borrowed smartphone seemed to be more eager to fill in the diary and also reported more episodes.

A last indication of the quality of the data, is the evaluation people made about the tests. Overall, the results of the evaluation survey showed that respondents did not consider the time-use app difficult to use (Table 3). Although the number of respondents was quite small, and in particular the number of people who experienced difficulties, some findings are interesting to mention. A frequently reported problem for both smartphone owners and inexperienced users was that the time interval of ten minutes was considered too short. However, this is a general HETUS guideline for time-use surveys. Smartphone owners had more problems in finding a suitable category for their activities compared to the inexperienced users, whereas inexperienced users had more difficulties in changing their activities in the day overview. The installation and start of the app was one of the easiest tasks, even for the inexperienced smartphone users.

The video which demonstrated the use of the smartphone for time use research was evaluated as particularly helpful by most of the respondents (not shown). For example, almost 70 percent of the inexperienced users found the video helpful for using the app or recording activities (68 percent and 69 percent, respectively), compared with 58 percent and 53 percent among the smartphone owners. Additionally, 66 percent of the inexperienced users evaluated the video as helpful for using the (borrowed) smartphone. As might be expected, the figure was much lower for smartphone owners (30 percent).

The results from this evaluation questionnaire induced us to conduct qualitative in-depth interviews with some of the respondents. Similar to the questionnaire findings, the in-depth interviews showed that the app was easy to use and people enjoyed participating in this type of research using smartphones to record their time use. The app was intuitive to use, which increased the positive feelings about the overall usability. In general, the interviews did not reveal major differences between the experienced and inexperienced smartphone users.

Collecting Survey Data by a Smartphone Feasible?

Based on the tests we conducted the title question can be answered positively: It is possible to conduct (time-use) research with an app on the smartphone for both experienced and inexperienced users. Respondents are able to use the app as an instrument to register their time use in a mobile diary and indications were found that the data quality between user groups is comparable. Some participants reported to experience problems with finding the relevant activities or considered the time intervals as too short, but the majority of the respondents were positive about the smartphone study and the usability of the surveyapp. Some differences were observed in registering time between smartphone owners and inexperienced users. Inexperienced users reported more episodes during the day and updated their diary more often than the smartphone users, which indicates better data quality. A possible explanation for this might be that those with a borrowed smartphone felt obliged to fill in their diary very accurately, which resulted in slightly more episodes reported.

Although the tests gave positive results, they were conducted with a relatively small number of participants which were not representative for the general population. This is why we implemented the smartphone app in a larger and representative survey among the Dutch population in 2012–2013. Data are collected from a random selection of the Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences (LISS)-panel, which is representative for the Dutch public. People without a smartphone can borrow one from CentERdata (the research institute which manages the LISS-panel). With this data, it will be possible to compare this data with the regular time use data collected by SCP and CBS in 2011–2012.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank CentERdata, attached to Tilburg University, and in particular Annette Scherpenzeel, Maarten Streefkerk, and Iggy van der Wielen.

This paper is based on an earlier SCP report see http://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=35103&type=org.

Further reading

Sonck, N. and H. Fernee. 2013. Using smartphones in survey research: a multifunctional tool. Implementation of a time use app; a feasibility study. The Netherlands Institute for Social Research/SCP, The Hague. Available at http://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=35103&type=org.

In a later stage, an app for iOS systems (iPhone) was designed and tested among 50 respondents.

_and_how.jpg)

_and_how.jpg)