Accurate behavioral measures of older Americans are vital to the making of sound, evidence-based policy decisions. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that 37% of the population will be aged 50 or older by 2030, up from about 28% in 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau 2004). A negative relationship between response rate and age has been identified in the survey methods and gerontological literature (Groves and Couper 1998; Herzog and Rodgers 1988; Redpath and Elliot 1988). Recent research on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) has shown that older persons sampled in the survey, particularly those age 50 or older, are less likely to complete the survey than younger persons (Murphy, Eyerman, and Kennet 2004). This article discusses potential barriers to participation among this population group and practices that could improve response rates with older respondents.

Declining Response Rates among Older Respondents

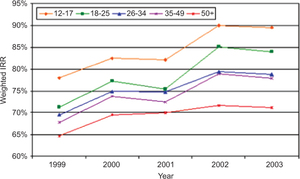

Data for NSDUH [1] are collected by field interviewers (FIs) through face-to-face interviews using CAPI (computer-assisted personal interview) and ACASI (audio computer-assisted self-interview) methodologies (Caviness et al. 2006). Figure 1 [2] shows the weighted interview response rates (AAPOR Response Rate #6) by age for the NSDUH from 1999 to 2003. Across all years, response rates were lowest for the 50+ age group. In 2001, a series of methodological enhancements were introduced to the study in order to increase response rates (SAMHSA 2003). Response rates from 2001 to 2002 were significantly higher for all age groups except the 50+ group. This suggests that the methodological changes had a larger positive effect on the response propensity of younger respondents thereby magnifying the already existing differences in response rate by age.

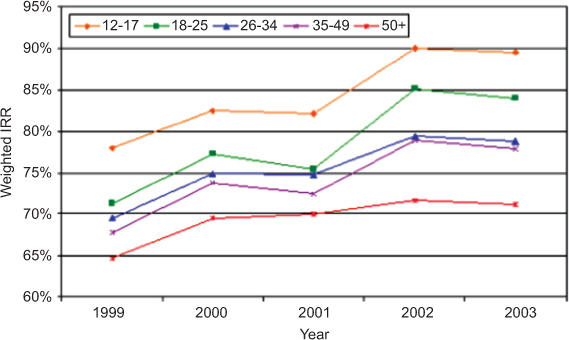

Figure 2 presents the components of nonresponse by age from the 2002 NSDUH indicating that lower response rates for the 50+ age group are due to higher refusal rates across the age group. The high rate of other incompletes among the 80+ is due to a higher rate of physical and mental incapability among that group. Among the 50+, refusal rates are highest for ages 55 to 69 and lowest for ages 70 to 79. The most common reported reasons for refusal across age groups are, “There’s nothing in it for me,” “I have no time,” and “Government/surveys are too invasive.”

Methods

Twelve focus groups were conducted in three cities to explore the issue of nonresponse among potential respondents aged 50 and older. Focus group participants were asked to watch a series of videotaped vignettes filmed from the perspective of a survey respondent. They were asked to describe the interaction and discuss reasons for participating or not participating in the survey. Specific questions focused on (1) the importance of the study topic, (2) privacy and confidentiality, (3) their opinion of the $30 incentive, (4) thoughts on aspects of the interviewer’s approach and the handheld device the interviewer was using to record information, and (5) study materials such as the lead letter and questions and answers (Q&A) brochure.

Findings – Reasons for Response and Nonresponse

Building rapport. Focus group participants said they would be more likely to respond to a FI who was prepared and polished, without being “slick.” They expect FIs to perform their task in a professional manner – polite, positive, and knowledgeable of the survey questions. FIs need to be aware that they are “guests” to the respondent’s property and understand how the respondent feels about someone unknown coming to their door. Participants also expressed they would not respond well to an FI who was timid or who presented a weak approach. Training interviewers to be sensitive to these matters may improve their ability to build rapport with the respondent.

Understanding and interest in the study topic. The two sources of information about the NSDUH survey – the brief FI introduction with the name of the survey and the lead letter – were perceived as vague by nearly all focus group participants. Many described their initial impression of the NSDUH survey as a study of prescription drug benefits and health insurance. Once the topic of the survey was fully explained to the participants, almost all agreed drug use and health is an important topic to research. All participants believed that understanding the survey topic in advance would increase their likelihood of participation, but this would not be the deciding factor. Nearly all groups recommended that the Q&A brochure be included with the lead letter.

Feelings of safety, trust, and confidentiality. Concerns were raised about the survey approach and physical safety, fear of “scams,” or other misuses of personal information. The importance of trusting the FI, the research organization, and the study purpose were expressed throughout all of the focus groups. Overall, confidentiality was not a major concern voiced by the participants. However, participants expressed concerns about the questions being intrusive, invasive, and too personal.

Understanding the study materials. Focus group participants reported that additional detailed information about the purpose and benefits of the study would facilitate trust and lend legitimacy to the research organization and FI. The lead letter was regarded as helpful and the Q&A brochure addressed the issues raised by the group. The refusal conversion letter appeared to address many participants’ concerns but some said it would not have convinced them to participate.

Understanding the participant selection process. Participants expressed confusion over the description of the selection process and the meaning of “random selection”. Most participants falsely believed RTI or the Federal government had access to their names and phone numbers, and thus FIs did not need to “beat around the bush” to obtain roster information. All participants in both age groups wanted the screening script and questions to get directly to the point. The perceived repetition of questions was a major issue, specifically for those in bigger households where roster questions are repeated for all household members. For some focus group participants, the possibility of having another person in their household selected for the interview would make a difference.

More money is not the answer for 50+ participants. In general, the offer of a $30 incentive was not seen as persuasive by the focus group participants. Few mentioned they would be convinced to do the interview for that amount. In some cases, participants felt that being offered an incentive was inappropriate. Others were suspicious of the incentive thinking it was a trick and that something other than completing the survey would be expected in return. Most participants agreed that money, while potentially persuasive, would not be sufficient to gain their participation. Although no solid suggestions for non-cash incentives were offered, participants felt that the most important factors affecting participation were the perceived legitimacy of the survey, trust in the motives of the FI, and an appreciation of the topic and value of the data.

Discussion

Among the important findings in this study, the general issue of trust appeared foremost among potential respondents’ concerns about participation. While trust is an obvious concern for any potential survey respondent, older individuals are particularly vulnerable to consumer fraud and may therefore be more wary of the survey’s motives. Addressing the issue of trust likely requires a multifaceted approach, including (1) public awareness of the survey, (2) clear and concise information about the study in contact materials, (3) interviewer contact procedures that focus on rapport building, (4) incentives that match respondents’ expectations, and (5) credible sponsoring and research organizations. While these are not new ideas (see Groves and Couper 1998), the tailoring of these concepts to the specific needs of older respondents is a unique application.

Several modifications could be made to the survey methodology for older adults. To address the concerns related to an interviewer showing up at a respondent’s household without an appointment, including a more precise “appointment time” in the lead letter or a telephone number for appointment scheduling. FI training could address concerns regarding the presumption of availability and the repetitiveness of the screener questions. To clarify the participant selection process, a better explanation of the selection process in the advance materials and the interviewer introduction may help to reduce confusion over the random selection process in surveys.

Though focus group participants may not be representative of “reluctant” participants, this study yielded potentially useful ideas for improving data collection strategies with survey respondents 50 and older. We found that the factors negatively affecting survey participation among this group are likely due to misunderstanding the survey topic and process, and concerns about safety and trust in the interview process. This information could be used across all surveys that experience low response rates with this age group.

To determine the effectiveness of the focus groups recommendations, each change to materials or procedures should be tested separately or in controlled designs where a few variables are manipulated simultaneously so any effects on participation rates can be observed in the absence of potential confounds or complex interactions. Changes that positively influence response rates could later be combined into a larger field test, the results of which would guide decisions on survey implementation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joe Gfroerer of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Hyunjoo Park and Kevin Wang of RTI International, Donna Hewitt, and Adam Safir for their assistance in preparing this article.

The NSDUH is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). RTI International is the data collection contractor.

Adapted from Murphy et al. (2004), which contains a detailed quantitative analysis of nonresponse among older respondents.