The behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) is an ongoing state-based random-digit-dialing (RDD) landline telephone survey. The data is used for monitoring national, state and local health objectives, and developing local health programs. States are required to call all monthly sampled telephone numbers within a month from their release to survey implementers. When samples are not completed within that month, states strive to complete them shortly thereafter. Despite this endeavor, BRFSS survey response and completion rates have been declining since 2002 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Other telephone surveys observed similar trends in response rates (Battaliglia et al. 2007; Groves et al. 2002). Recently, states expressed interest in exploring the effect of continuing the data collection longer than a month on the percentage of completed interviews and response rates.

Included among the factors contributing to this declining trend in the response rates cited by many studies are high refusal rates, increased telemarketing, use of new technologies, increase in single-person households, difficulty in contacting eligible respondents, decline in civic participation, lack of adequate leisure time, increased concern about privacy and confidentiality, demographic shifts in the U.S. population causing high language barriers, and physical and mental inabilities to complete the survey (Groves, Singer, and Corning 2000; Tourangeau 2004). These factors are often grouped into either refusal to cooperate, non-contacts or inability to participate (Groves and Couper 1998).

In 2007, the percentage of completed interviews of the total sample in the BRFSS survey was approximately 10%. Few states maintained or increased their 2006 completion rates (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). States and survey organizations are searching for ways to improve response rates. The impact of various methods on the response rates were examined (Kropf and Blair 2005). In BRFSS, the average number of calls per completed interview has increased recently in many states, indicating enhanced efforts to contact selected households. This, however, did not improve the completion or response rates (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Additionally, retraining interviewers, hiring experienced interviewers and increasing hourly wages become routine practices for survey organizations and states as a potential means to improve response rates. Prolonging the length of time allotted for data collection also resulted in an increase in the response rate (Keeter et al. 2000).

In this paper, we examine whether continuing the data collection beyond one month improves the completion and response rates in BRFSS. If significant gains are observed, loosening the current BRFSS guidelines might become necessary.

Methods

We used the 2007 BRFSS data, a cross-sectional survey conducted in 50 states, Washington DC, and U.S. territories in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A representative sample of household landline telephone numbers is selected using a modified RDD method (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006). Within the selected household an adult is selected randomly to be interviewed within 31 days, which is the current practice for data collection. We excluded Michigan and Louisiana from the analysis because of quarterly (3 months) data collection length for Michigan and data collection issues for Louisiana.

For each state, we estimated the percentage of the sample that was called and given a final disposition code (American Association of Public Opinion Research 2008), percentage of completed interviews and response rates in 31 days, 32 days–41 days and >41 days.

The numerator for the percentage of completed interviews was the completed and partially completed interviews (American Association of Public Opinion Research 2008). For the response rate numerator, we used the completed and partially completed interviews, and records indicating termination of interview in which at least 50% of the core questions prior to demographics section were answered. Because some states did not call all telephone numbers in the sample and could not have interview dates, we used a single denominator, as defined by American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) (American Association of Public Opinion Research 2008), to calculate response rates for 31 days, 41 days, and >41 days. We chose the single denominator because we were interested in the increase in the response rates as a result of the prolongation of the length of the data collection. We used SAS (SAS 9.1 1999) to calculate our estimates.

Results

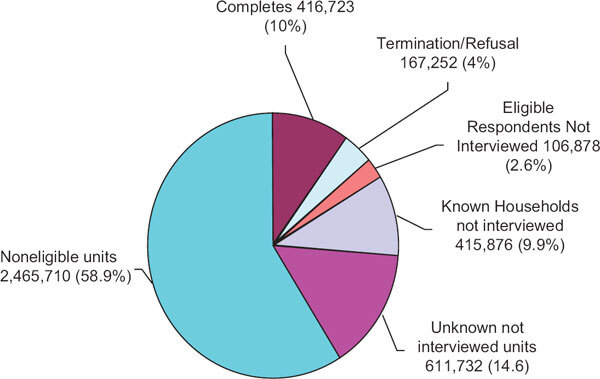

In 2007, excluding Michigan and Louisiana, a total of 4,184,515 telephone numbers were selected from the U.S. landline telephones for the BRFSS survey. We excluded 344 records with missing disposition codes and analyzed 4,184,171. Of these, 416,723 (10%) interviews were completed; 167,252 (4%) terminated or refused; 106,878 (2.6%) were eligible respondents not interviewed; 415,876 (9.9%) were households where the presence of eligible respondents could not be determined; 611,732 (14.6%) were numbers that could not be determined whether they belong to households or not; and 2,465,710 (58.9%) were ineligible numbers (Figure 1).

Of the total telephone numbers analyzed, 4,173,620 (99.7%) received a final disposition code in 2007. Of these, 3,184,631 (76%) were called and had valid information on the interview date and 988,989 (24%) were not called. Of the numbers called, 2,828,171 (89%) received final disposition code within 31 days, 258,041 (8%) between 32 days to 41 days, and 98,419 (3%) more than 41 days. The percentage of telephone numbers receiving final disposition varied by state (Table 1).

Of the 3,184,631 numbers called in 2007, 415,371 (13%) completed the interviews, of which 94.6% were completed within 31 days, 3.7% were completed between 32 days to 41 days and 1.7% completed after 41 days. The percentage of interviews completed in these three time intervals varied between states (Table 2). The median increase in the percentage of completed interviews was 3.4%.

The CSARO response rates by state and length of data collection are shown in Table 3. The median CASRO response rate in 2007 for the US was 51%. It increased 1.4% after continuing data collection longer than 31 days.

Discussion

Continuing the data collection beyond 1 month shows a minimal contribution to the percentage of completed interviews and CASRO response rates, but the contribution is slightly higher on the percentage of the sampled telephone numbers that were given final dispositions than both of the former estimates. The median increase in the percent of completed interviews and the percentage of the sample that was given final disposition codes are 3.4% and 6%, respectively. Similarly, the median increase in the response rate is 1.4%. As the response rate and percent of completed interviews indicate, two essential measures of survey success, these gains could not warrant a change in the current guidelines, which is to complete the samples within a month. Improving the efficiency of the survey operation could result in similar gains within the limits of 1 month duration of data collection. Some states completed their samples within a month, and those adopted 3 months (quarterly) data collection length were not different than those following the current 1 month practice in the percent of completed interviews. Also, states that gave final disposition to their samples within a month include those that used large and small samples in their BRFSS survey, and did not confine themselves to call telephone numbers prescreened as working numbers and are likely households.

Furthermore, changing the current guidelines might compromise standardized practices, a major strength for the BRFSS data collection, which allowed survey analysts to compare parameters across states and territories. It could also bring unnecessary disruptions and confusion in survey operations and efficiency in the course of its implementation and introduce additional variation to estimates.

Although the majority of states continue to collect data after 31 days, the remaining numbers in their samples are completed shortly after 31 days, thus preserving comparability of information by time reasonably across states and counties. Seventy three percent of the sample called after 31 days received final disposition within 10 days from the 31 days. Similarly, 80% of the interviews completed after 31 days were completed within 10 days from the 31 days. Studies that examined the effects of the extended length of data collection on response rates showed varied effects (Groves, Lyberg, et al. 1988) and (Collins et al. 1988), which is consistent closely with our findings across states.

The observed minimal increase in the percent of completed interviews and CASRO response rate from the extended field period might not bias U.S. estimates in diseases, risk factors and disease-risk associations because the majority of completed interviews (95%) were captured within 31 days. Few states could experience biases in state and local estimates because of the wide variations in the proportion of completed interviews captured after 31 days. However, further studies are needed to verify the existence and determine the extent of such bias. Likewise, further studies are needed to examine the differences between the information captured before and after 31 days of data collection.

Our study has limitations. The analysis excluded two states and telephone numbers that were not called. We did not group the states by the organization or agency that collects the data, which could vary in their survey operation strategies. Therefore, generalization of the findings should consider these limitations. In addition, the BRFSS survey uses RDD landlines, and findings might not be applicable to surveys using other modes of data collection.

After 31 days of calling, telephone numbers that were hard to reach are the ones to be called further and are less likely to end up in completed interviews as the results show. Thus, continuing the data collection longer than 31 days is inefficient for landline telephone surveys. BRFSS survey shares similar problems with other landline surveys. Incorporating other modes of data collection, such as cell-phone and mail modes, to RDD landline could bring some solution to the declining response rate problem.

CDC disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.