Recent coverage issues, such as cell phone only households, have raised concerns about the landline random digit dialing (RDD) sampling frame that previously has been a mainstay of telephone research. Address Based Sampling (ABS) has been suggested as a possible solution to these issues. We decided to explore the potential benefits and detriments of using ABS techniques for phone data collection. We concluded that we were fairly successful in driving the ABS unmatched sample respondents to the phone, but that the response rates were still very poor on the ABS unmatched sample. The response biases by different demographics were equivalent in the two sample frames and there were no significant differences in the grocery shopping behavior. Lastly, although the cost for dialing the matched ABS sample was less than the RDD sample, overall the ABS design was more expensive.

In particular we were interested in the ability of ABS sampling to reach cell phone only households, less acculturated Hispanics, and other sub-populations that may be under-represented in normal landline RDD dialing. We used a population of retail grocery store shoppers in the state of Texas and a questionnaire developed to find the drivers of grocery store choice, examine the purchase history of product brands, compare coupon usage, and measure online shopping behavior. We chose Texas for its higher less acculturated Hispanic population and breadth of geographic, education, and other socio-economic variables.

We anticipated cost, response rate, and data differences across the different methodologies. Knowing that expanded ABS sampling techniques do take more time in the field, we expanded the RDD study time to more closely match the ABS time constraints to make that as consistent as possible. We also used the same bilingual interviewers from a domestic phone center for both frames to control for any interviewer or phone center effect that might exist. We discuss the results of the surveys and conclude with lessons learned from our experience.

Literature Review

The industry has noticed declining response rates to consumer surveys for a variety of reasons (Swanson and Holton 2005). In response to increased concerns about growing survey non-response and eroding coverage of random digit dial (RDD) telephone sampling frames, researchers are returning to mail surveys or multi-mode surveys with an address based sampling (ABS) frame (Link et al. 2006). Most applications of ABS use the new United States Postal Service (USPS) database called the Delivery Sequence File (DSF) to create a probability sampling frame. Traditionally, mail surveys of the general public have been limited due to the lack of a complete sampling frame of households. Recent advances in electronic record keeping, like the USPS DSF, have allowed researchers to develop a sampling frame of addresses whose coverage rivals or possibly exceeds that obtained through RDD sampling methods (Link et al. 2008).

As part of the 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a pilot study was conducted to test the efficacy of address based sampling in conducting surveys among adults aged 18 years and older across a wide geographic area (Link et al. 2008). They compare the use of a traditional, RDD telephone survey methodology to an approach using a mail version of the questionnaire completed by a random sample of households drawn from an address-based frame. They observed higher response rates using ABS in low-response-rate states (<40%) than RDD (particularly when two mailings are sent). Additionally, they observed that the ABS frame provides access to the cell phone only households missing from the random digit dialing frame. Moreover, they observed cost savings over the telephone approach. However, these studies were done on different modes. We wanted to explore the frame differences in one mode.

Methodology

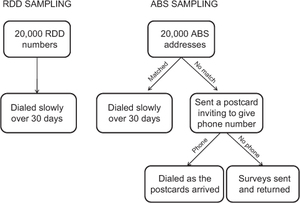

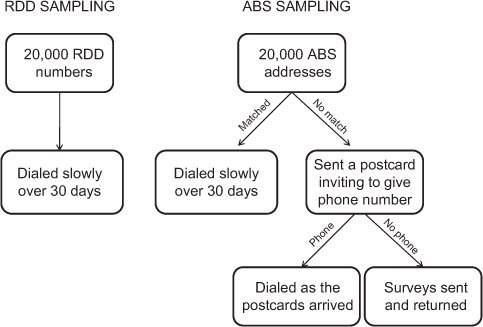

We used two sampling methodologies: the landline RDD design and the ABS design. The landline RDD sample was obtained from our usual vendor (SSI) using current RDD techniques while the ABS sample was obtained through a vendor of the UPSP–DSF (Melissa Data). Both designs started with a sample of 20,000 phone numbers or addresses, respectively, from a stratified sampling design with each county proportional to the overall state population. No additional strata such as gender or age or propensity adjustment by county were used because of lack of information available on the sample. The phone portion of both samples was conducted over the same time period. The mail data collection continued for approximately 1 extra month but 75% of the mail data came in the same 30 day time period that the phone portion was conducted. Figure 1 depicts how the different samples were treated to obtain the necessary completes.

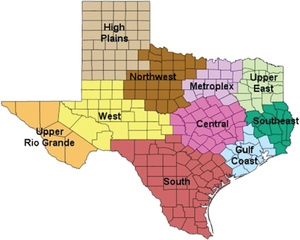

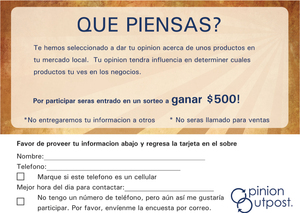

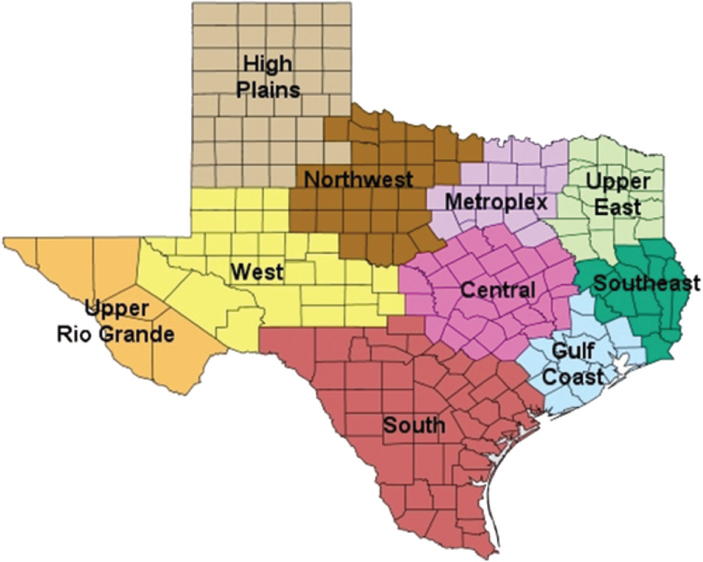

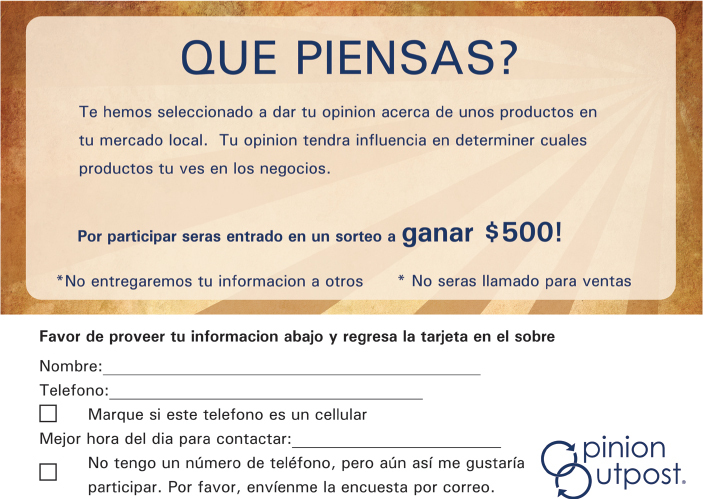

The landline RDD sample was dialed slowly over 30 days for a total of 600 completes using typical RDD methods with complete stratification targets by the 10 specified regions in Figure 2. The ABS fame included PO boxes and any other deliverable address, so it is possible that some respondents who have a PO box and a normal mailing address had a greater chance of being selected. The ABS list was first matched for phone numbers by Melissa Data to obtain a sub-sample to call directly. All unmatched addresses were then mailed a double-sided postcard invitation seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4 to participate in the study. Both sides contained the same information, but one side was completely in Spanish. A pre-paid return envelope was included with the postcard. The postcard included an option to request the full survey mailed to them if they did not have or wish to provide a phone number for us to call. These harder to reach respondents were offered a cash sweepstakes as an incentive to increase response rate.

In fielding the ABS portion we collected a disproportionate number of completes from the matched sample. The original sample file had 45.8% of the sample matched to a phone number, but 77.2% of the completed surveys came from the matched phone sample. We weighted the data to correct for this proportion and for the small differences in geographic strata, resulting in moderate weighting (RDD: average weight=1 and standard deviation=0.007, ABS: average weight=0.873 and standard deviation=0.667).

Results

Table 1 shows the response rates for both sampling frames. Overall response rate (using AAPOR Definition 3) to the landline RDD dialing was 7.9%, and on the phone ABS matched sample it was 8.9%. Response rates to the postcards was quite low (2.1% overall) and will need to be increased for a more reliable sample. Apparently one mailing of the well designed postcard and the sweepstakes offered were not enough to engage this hard to reach segment. Our efforts to drive this segment to the phone mode also met mixed results. A large portion of the respondents to the postcards (86/233=37%) refused to give a phone number or reported not having a phone number. On the positive side, our re-contact rate of these postcard recruits was quite high (67%). In the end, 9.1% of the completed ABS survey through a mailed mode rather than a phone mode. Thus, we did not eliminate the mode effects, but we did greatly reduce any mode effects. Combining the higher response rate from the matched sample (8.9%) with the lower response rate from the unmatched sample (1.5%) resulted in an overall response rate of 4.0%. These low response rates (7.9% for the RDD frame and 4.0% for the ABS frame) contributed to the demographic skew in the sample.

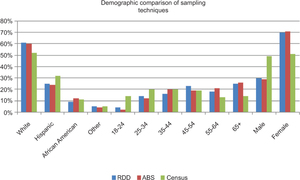

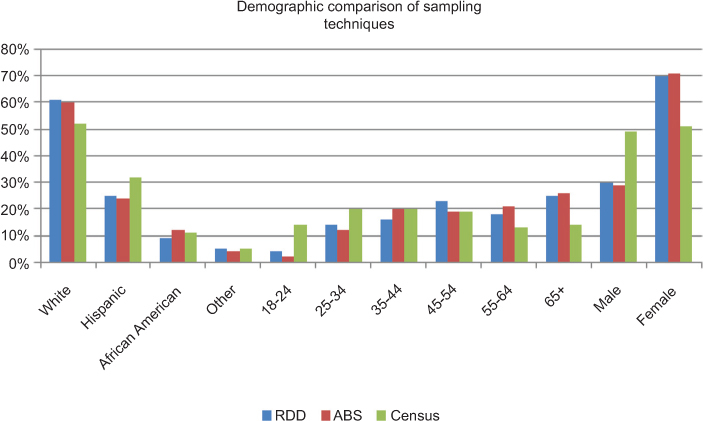

The demographic composition of the resulting sampling frames is found in Figure 5. Because no sampling limits were placed on the demographic distribution neither sampling frame resulted in a good demographically unweighted representation of the population. The response bias in both samples caused deficiencies in the 18–24 age category, females, and Hispanics. Interestingly, the non-response bias from both frames was approximately equal, resulting in comparable samples.

The important response variables related to grocery shopping (like monthly grocery budget, grocery store of choice, drivers of grocery store choice, and product purchase history) showed no differences in the response variables of interest. However, there were some important communication and socio-economic differences in the sampling frames. In general, the ABS sampling frame was more acculturated, but also lower income. As expected, the cell phone only households are much higher in the ABS fame, but surprisingly Internet availability and shopping were lower. Table 2 shows the significant differences between the sampling frames.

Costs and Fielding Implications

Table 3 shows the cost associated with each sampling frame in fielding the data. One of the biggest unexpected findings was how cost effective the ABS frame was to dial. We originally were excited that we could get cost savings by changing the source of our phone sample, but ignoring the unmatched portion of the ABS sample resulted in significant bias. While the ABS sampling frame had a lower cost to dial, the amount of time and money spent on the mailings erased the dialing cost advantage of the ABS frame. Another important fielding consideration for the ABS frame is that the increased timeline and inability to obtain targeted sample inhibited our ability to effectively control demographic targets. Some researchers have found that phone matching ABS sample across multiple vendors can significantly increase the number of phone matches and thus help create a bigger cost advantage (Link et al. 2008).

Conclusion

There are situations where ABS sample would be preferable to landline RDD dialing (especially when the cell phone only population is essential), but turnaround time and costs will increase. For projects targeting general population demographics landline RDD appears to do as good a job as ABS in reaching the target population (grocery shoppers) with little perceivable difference in demographic or key response variables. Other studies, such as Internet usage, might need to use the ABS frame to reduce the coverage bias. Our original premise that ABS may help get Hispanics, particularly less acculturated Hispanics, does not appear to be the case. They appear to respond at the same rate in each frame and were actually more acculturated in the ABS frame.