In planning surveys with a cell telephone sample component, survey researchers often think in terms of a cost ratio – the cost per complete interview in the cell phone sample relative to that in the landline sample. AAPOR’s 2010 Cell Phone Task Force Report includes a discussion of the factors that affect this cost ratio; however, the report does not discuss the impact of the rarity of the target population on the relative costs of cell telephone surveys. That is, the cell-to-landline cost ratio may be different for a rare population survey compared to a general population survey, and the difference will depend on the size and characteristics of the target population being studied. In this paper, I describe why this is true and present a cost-ratio formula that separates the components expected to vary depending on the nature of the rare target population from the components that should be relatively constant across surveys with differing target populations. I discuss the usefulness of this formula in planning for and monitoring cell phone data collection, and I provide a demonstration.

Introduction

In planning surveys with a cell phone sample component, survey researchers often think in terms of a cost ratio – the cost per complete interview in the cell phone sample relative to that in the landline sample:

Cost Ratio=Cost per CompletecellCost per CompleteLL(1)

Because the largest component of survey costs is interviewer time, we sometimes think in terms of interviewer hours per complete (HPC) and the HPC Ratio:

HPC Ratio=HPCcellHPCLL(2)

AAPOR’s 2010 Cell Phone Task Force Report includes summary statistics (reproduced in Table 1) for the HPC ratios from 26 dual frame RDD surveys conducted in the U.S. Note that all of the HPC ratios were greater than 1 (i.e., the HPC was greater for the cell phone sample than for the landline sample), and that there was considerable variation in the HPC ratio across the 26 surveys.

The AAPOR 2010 Cell Phone Task Force Report also includes a discussion of factors that can increase the HPC ratio – i.e., factors that raise the interviewer cost of cell phone data collection relative to that of landline data collection. These factors include:

- In the U.S., cannot auto-dial or predictively-dial cell phone numbers

- No pre-screening of non-working and business numbers for cell phone samples

- Lower contact rates in the cell phone sample

- Possibly lower eligibility rates in the cell phone sample due to minor-only cell phones, lack of geographic targeting, and screening for cell-phone-only households

- Possibly lower cooperation rates for the cell phone sample

The report does not discuss the impact of the rarity of the target population on the relative costs of cell phone data collection: all else being equal, surveys of rare populations may encounter different cell-to-landline HPC ratios compared to general population surveys.

Impact of the Rarity of the Target Population on the HPC Ratio

Consider two landline RDD surveys: a general population survey (e.g., a survey of adults) and a rare population survey (e.g., a survey of households with Hispanic children). Figure 1 shows what the distribution of interviewer time might be for such surveys. Because nearly every household is eligible for the general population survey, a relatively small proportion of interviewer time is spent identifying eligible households; the majority of the time is spent conducting interviews. In a rare population survey, however, where perhaps fewer than 1 in 20 households is eligible, the vast majority of the interviewer time may be spent trying to identify eligible households, with a small proportion of the interviewer time spent actually conducting interviews once the eligible households have been identified.

Now suppose each of these two surveys is planning to field a cell phone sample component, and consider the cell-to-landline HPC ratio for the general population survey versus the rare population survey. (For simplicity, in what follows we assume that aside from the target population of interest, all aspects of the data collection protocol are identical between the two surveys, including calling rules, within-household-selection rules, offers of incentives, etc. We allow these rules to differ between the landline sample and the cell phone sample, but we assume that protocols for the landline sample are the same between the two surveys and the protocols for the cell sample are the same between the two surveys.) To see how moving from a general population survey to a rare population survey can affect the cell-to-landline HPC ratio, we can divide the interviewer costs of a survey into two components: screening (i.e., attempting to identify eligible households) and interviewing (i.e., attempting to complete interviews for identified eligible households):

C=(c′n′)+(c′′n′′)(3)

where single primes denote the screening stage, double primes denote the interviewing stage, and

C= total interviewer costs

c′= screening cost per screener completion

n′= number of screener completes

c″= interviewing cost per interview completion

n″= number of interview completes

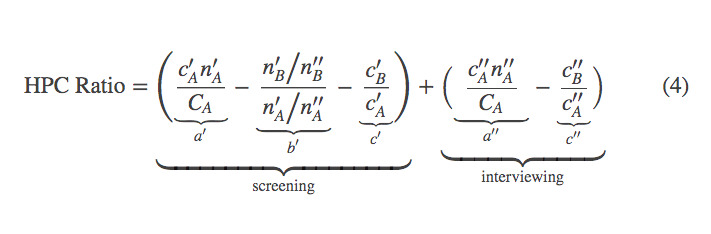

The cell-to-landline HPC ratio can then be written as:

where A denotes landline sample, B denotes cell phone sample, and

= screening cost per screener completion in the landline sample

= screening cost per screener completion in the cell phone sample

= number of screener completes in the landline sample

= number of screener completes in the cell phone sample

= interviewing cost per interview completion in the landline sample

= interviewing cost per interview completion in the cell phone sample

= number of interview completes in the landline sample

= number of interview completes in the cell phone sample

= the total cost in the landline sample

Components ( a ′) and ( a ″) are the proportion of total landline interviewer costs that are devoted to screening and interviewing, respectively, and, as shown in Figure 1, may vary widely depending on the rarity of the target population. That is, in rare population surveys, a greater proportion of interviewer time is devoted to screening than in general population surveys.

Component ( b ′) is the ratio of the number of screener completes needed to achieve one interview complete in the cell phone sample relative to that in the landline sample, and depends on the eligibility rate and cooperation rate in the cell phone sample relative to the landline sample. Depending on the particular rare population being targeted, this component may be larger or smaller for the rare population survey than for a general population survey. For example, the incidence of binge drinking may be high enough in the cell phone sample relative to the landline sample that in a survey of binge drinkers component ( b ′) would be lower for the rare population survey than for the general population survey. The opposite could be true for a survey where the eligibility rate is likely higher in the landline sample than the cell phone sample, such as a survey of elderly adults.

Component ( c ′) is the ratio of the screening cost per completed screener in the cell phone sample to that in the landline sample; component ( c ″) is the ratio of the interviewing cost per completed interview in the cell phone sample to that in the landline sample. These can be thought of as stage-specific cost ratios and should be relatively constant across surveys with differing target populations, because they do not depend on the survey’s eligibility rate.

On balance, compared to a general population survey, the HPC ratio for a rare population survey could increase or decrease depending on the relative values of these components. Prior to beginning cell phone data collection, it is important to consider what the values of these components may be for the target population of interest in order to anticipate what the HPC ratio will be for the survey.

Demonstration

Figure 2 demonstrates how equation 4 can be used to anticipate the HPC ratio for a dual-frame survey. Suppose that based on other dual frame surveys conducted using similar data collection protocols, we know that components ( c ′) and ( c ″) are 3.0 and 1.25, respectively. (That is, assume the screening cost per screener complete in the cell phone sample will be 3.0 times that in the landline sample, and assume the marginal interviewing cost per interview complete in the cell phone sample will be 1.25 times that in the landline sample. Recall that for a given data collection protocol, these components should not depend on the target population of interest.) Figure 2 shows the resultant HPC ratio for various values of components ( b ′) and ( a ′). As the target population gets rarer and a larger proportion of total time is devoted to screening (i.e., as a ′ increases), the HPC ratio can greatly increase or decrease, depending on component ( b ′), the number of screener completes needed per interview complete in the cell phone sample relative to the landline sample. If we have some prior knowledge about what the eligibility rates are likely to be in the landline and cell phone samples, we can estimate the values of ( a ′) and ( b ′) and thus predict the HPC ratio.

Conclusion

Overall survey cost (in terms of interviewer time) is equal to the cost of identifying eligible households plus the cost of interviewing eligible households once identified. On a per-interview basis, cell phone data collection is usually more expensive than landline phone data collection, but the cell-to-landline cost ratio can depend significantly on the particular population that is being targeted by the survey; in particular, the cost ratio depends on the rarity of the target population and the relative eligibility rates in the landline and cell phone samples. When planning cell phone data collection for a rare population survey, survey researchers should not assume that the cell-to-landline cost ratio will be the same as for a general population survey, but should instead consider how the cost ratio can depend on the particular rare population being targeted.

Notes

- In this paper, I have divided the data collection operation into two stages: screening (i.e., attempting to identify eligible households) and interviewing (i.e., conducting interviews with eligible households, once identified). However, if desired, the data collection operation can be divided into more stages (e.g., resolution to identify households, screening to identify eligible households, and interviewing), and equation 4 can be generalized as:

\begin{equation}\text{HPC Ratio}=\displaystyle\sum_i \left(\frac{{c}_{A,i}{n}_{A,i}}{{C}_{A}}–\frac{{n}_{B,i}\big/{n}_{B,i}}{{n}_{A,i}\big/{n}_{A,i}}–\frac{{c}_{B,i}}{{c}_{A,i}}\right)\hspace{15mm}(5)\end{equation}

as:

where i denotes the stage of the survey.

- In the demonstration section, the example assumed a cell-to-landline cost ratio for completing screeners of 3.0 and a cell-to-landline cost ratio for completing interviews of 1.25. While these cost ratios should not depend on the target population of interest, they will depend on other factors such as whether the landline sample is being auto-dialed, and if so, whether it is being predictively-dialed; whether pre-screening of non-working and business numbers is being employed in the landline sample; the calling rules that are used; the experience and efficiency of the interviewers; the within-household-selection method; and the use of advance letters, monetary incentives, etc. to increase participation.