Introduction

Like most survey research organizations, Mathematica Policy Research monitors telephone interviewers to ensure that they collect high-quality data. Monitors identify problems with survey questions, recommend interviewing techniques, and retrain interviewers whose performance do not meet expectations. Because monitoring is a critical quality assurance tool, we are interested in understanding the behavior of monitors – specifically, their ability to provide effective and consistent feedback on interviewers’ performance. Mathematica implements several best practices to promote monitoring consistency:

- Monitoring at least 10 percent of each interviewer’s work using a standardized form and rating scale.

- Employing monitors with previous interviewing experience and providing comprehensive training for monitors.

- Providing immediate feedback to interviewers on techniques that were performed well during the interview and areas that need improvement.

The monitors evaluate interviews using a form with the following sections: (1) basic session information, (2) behavior coding system to identify types of errors, (3) voice characteristics and rapport, (4) completion of introduction and conclusion tasks, (5) comments on overall performance.

After completing the monitoring form, the monitors assign an overall rating for the session, using a five-point scale: (1) unacceptable, (2) does not meet expectations, (3) meets expectations, (4) very good, and (5) excellent. Despite these best practices, anecdotal evidence from interviewers and monitors suggests that monitors use a range of different criteria when rating interviewers, which could have an impact on data quality, the reliability of interviewers’ performance ratings, and staff morale and retention.

Research on understanding monitors’ behavior or effects is not extensive. Most studies have focused on describing monitoring processes or methods, such as the key elements of an effective monitoring system (Cannell and Oksenberg 1988; Fowler and Mangione 1990; Lavrakas 2010), or how organizations monitor the quality of their work (Burks et al. 2006; Steve et al. 2008). Tarnai (2007) discussed the advantages and disadvantages of monitoring both complete and partial interviews and examined interviewers’ reactions to the monitoring process. Thus, little is known from research about the factors that affect monitors’ judgments and the feedback they provide to interviewers. To explore these issues and to improve our quality assurance procedures, we conducted focus group discussions with monitors and interviewers.

Methodology

In April 2011, we conducted four focus group discussions (see Table 1): two with monitors (active monitors and monitor supervisors) and two with interviewers (novice and experienced).

The 12 active monitors had between 1 and 17 years’ experience interviewing and monitoring. The three supervisors had between 4 and 10 years’ experience interviewing and monitoring in addition to experience as monitoring supervisors (between 3 and 5 years). The monitors received specialized training on Mathematica’s monitoring procedures and systems, including procedures for applying monitoring standards consistently and guidelines for providing constructive feedback to interviewers.

The eight novice interviewers had <1 year of interviewing experience, while the eight experienced interviewers had between 1 and 10 years’ experience. Each interviewer received both general interviewer training and project-specific training.

The focus group discussions were conducted by teams of experienced researchers, and the discussions were audiotaped and then analyzed. Our analysis consisted of three main stages: (1) preliminary review of interview notes and audiotapes, (2) identification of key themes and issues, and (3) confirmation of findings with expert monitor supervisors.

Results

Criteria monitors use to rate interviewers

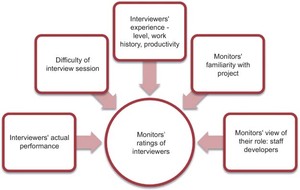

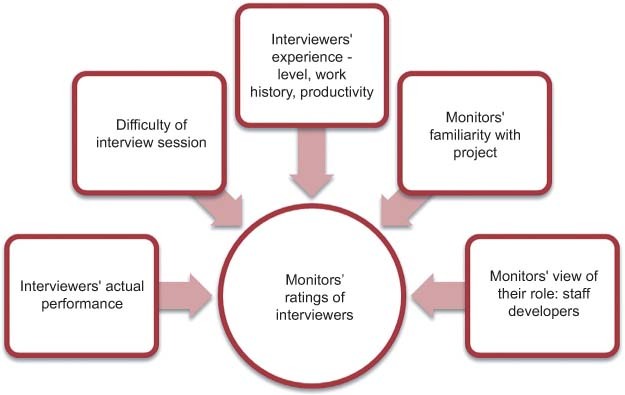

Monitors in both groups discussed five main factors that influenced the ratings they gave to interviewers (Figure 1).

- Interviewers’ actual performance. Both groups of monitors said their ratings are based on the interviewers’ actual performance. They were in agreement about the most serious common errors: (1) not reading verbatim, or skipping questions; (2) lack of probing; (3) a rude tone; and (4) not being familiar enough with the project to explain the study. The monitors felt that all these errors could be fixed with appropriate feedback and possible retraining.

- Difficulty of the interview session. Both monitors and monitor supervisors agreed that the difficulty of the interview is a factor when assigning a score. Interviewers who can follow the interview protocol during a difficult interview (a refusal conversion, for example) are more likely to receive a rating of 4. Some monitors mentioned being more lenient about an interviewer’s sloppy introductions if the interviewer was conducting a challenging type of survey.

- Interviewers’ experience level. The monitor supervisors and some active monitors noted that they are more likely to be lenient in their scoring with new interviewers so as not to discourage them. However, some active monitors felt that the interviewers’ experience level should not factor into their score, but should be considered in providing feedback to interviewers. For example, monitors may emphasize the positive qualities of interviews and may be less harsh when discussing errors with new interviewers than with more experienced interviewers.

- Interviewers’ work history. Both groups of monitors noted that there are some interviewers who do a very good job but continue to make the same errors. Monitors may assign these interviewers a lower rating than their overall performance warrants, in order to trigger an automatic notice to their supervisor for appropriate follow-up.

- Interviewers’ productivity. Both groups of monitors mentioned that sometimes there is more emphasis on production than on quality. The monitor supervisors suggested that monitors are sometimes more lenient when rating interviews administered by productive interviewers. The active monitors questioned whether the supervisors of productive interviewers would take action if a highly productive interviewer consistently received low scores.

- Monitors’ familiarity with project. Both monitor supervisors and active monitors mentioned the importance of their own familiarity with the project when explaining their interviewer rating. Familiarity with the project gave them confidence in their evaluations and a context for understanding project-specific expectations for the interviews. Monitors unfamiliar with the project based their ratings on interviewer best practices.

- Monitors’ view of their role. In general, the active monitors view themselves as coaches or mentors to the interviewers. They strive to improve morale and develop the interviewing staff. The active monitors believe that part of their role is to help the interviewers succeed, rather than punish them by assigning a low rating. While the monitoring supervisors agreed that the monitors’ role should be mentoring and inspiring good behavior, they felt that the focus of feedback to interviewers is more often on correction.

Both groups felt that it was best to start a feedback session by reviewing the positive aspects of the interview, and then to discuss areas that need improvement. They believe this approach builds interviewers’ self-esteem and makes them more receptive to critiques of their performance. However, both monitor groups admitted to being reluctant to assign lower ratings, because they do not want to discourage staff who may need extra support.

Consistency of monitors’ feedback to interviewers

To find out how well the monitors provided clear and constructive feedback to the interviewers, we conducted focus groups with new and experienced interviewers. Both groups of interviewers noted that the monitors were consistent in providing feedback immediately after the interview and discussing the positive aspects of the interview first. However, the interviewers reported that there is often variation from monitor to monitor in how the feedback is delivered.

Some monitors communicate like a coach or mentor, while others have a more punitive approach to feedback. Also, different monitors tend to focus on different behavioral issues (i.e., some focus on probing issues while others focus on reading verbatim). Last, usefulness of the feedback can vary by monitor; some monitors focus on issues that the interviewers consider to be trivial. In general, the interviewers find the feedback helpful and tend to pay attention to the monitors’ comments rather than to the overall rating. We did not find any important differences between the new and experienced interviewers in their views of the monitoring process.

Conclusion and Discussion

The goal of this research study was to explore the criteria monitors used to evaluate interviewers and the consistency of their feedback. Based on focus group discussions with monitors and interviewers, we found that:

- When assigning ratings, monitors consider factors beyond the interviewer’s actual performance, such as the interviewer’s familiarity with the project, past performance, and experience level.

- Monitors define their role broadly and seek to develop stable, experienced interviewers in order to obtain high-quality data.

- While monitors employ consistent procedures for providing feedback to interviewers, the style, emphasis, and usefulness of their feedback vary.

Based on our findings, we have several recommendations:

- When examining the issue of monitor consistency, it is helpful to look beneath the surface. Using exercises, such as having monitors evaluate and discuss the same interviews, is an effective way to explore monitors’ decision-making and the criteria they use. These criteria can then be compared to any rating scales that the monitors are expected to use, to see whether they are focusing on elements of the interview consistent with the criteria in the rating scales.

- If necessary, alter rating scales to ensure consistency across monitors. If the monitors note criteria they use to rate interviewers who are not already included in the rating scale, consider revising the scale to include these criteria or find another way to standardize the rating process so that all monitors are considering the same criteria when rating interviewers.

- Provide training to monitors on how to provide feedback. Some monitors will naturally be better than others at delivering feedback to interviewers. However, all monitors can be trained on how to provide clear and constructive feedback. Providing monitors with a framework on how to deliver feedback and providing them with training opportunities to learn and practice these skills will result in more consistent and useful feedback to the interviewers.