In a recent Survey Practice article, Moore (2011) argues that policy polling is not living up to its democratic potential (Moore 2011). As he sees it, and we generally agree, polling frequently manufactures a fictitiously interested and attentive public. Pollsters’ sins include pushing respondents to reveal preferences when no real opinion exists and failing to examine the (lack of) intensity of respondents’ answers.

While Moore’s criticisms of contemporary survey research are not entirely unique, more novel and controversial is his method of asking respondents if they would be upset if their preferences went unheeded in order to distinguish between “permissive” and “directive” opinions. Further, some pollsters are skeptical about the applicability of his critique to every issue (Traugott 2009). The question is an important one. If Moore is right that public opinion usually reflects the questionable practices of survey researchers rather than the aggregation of thoughtful and deeply held preferences, why should public opinion, as it is most commonly measured, influence policy debates?

In this article, we examine whether non-attitudes affect depictions of public opinion in North Carolina about free trade policies. Rather than following Moore’s practice of using emotional reactions to characterize the intensity of an opinion, we more simply exploited a combination of traditional but underutilized approaches to identifying the percentage of the population lacking genuine opinions. As we demonstrate, the failure to screen for non-attitudes greatly exaggerates the percentage of people who have meaningful preferences about trade. In addition, we show how varying core measurement strategies can easily turn pluralities into majorities with different preference distributions, and create the misleading impression that voters are fools and that policy makers are acting against the majority’s (or voters’) interests.

Non-Attitudes?

As a starting point for most of these discussions, studies of polling have uncovered a worrisome pattern of unstable opinions about policy preferences within and across surveys and over time (Best and McDermott 2007; Converse 1970; Norpth and Lodge 1985). Respondents have even been found willing to offer up opinions to pollsters about non-existent policies (Morin 1995). In the worst case scenario, public opinion is merely an illusion, the product of questionable survey practices combined with respondents’ eagerness to respond to most any question, regardless of whether they are just making one up on the spot or not (Bishop 2005; Moore 2008).

Of course, in academic circles the meaning and origins of response instability is debatable (Converse 1964; Sniderman, Tetlock, and Elms 2001; Zaller and Feldman 1992). Nevertheless, it is understood that non-attitudes, should they widely exist and be the source of response instability, have the potential to bias research findings and distort policy debates by generating illusory majorities that are said to support particular courses of action.

To deal with the threat of non-attitudes, some of the earliest polling utilized screening questions to minimize the number of superficial responses. Respondents were asked ahead of time whether they had thought much about the topic, or if the issue was important to them. Those who admitted to not caring or not giving much thought to a topic would not be asked questions about it; why should they be?

Sometimes, but not often, researchers have compared responses of those who care and do not care about an issue (Benson 2001). In one such study about trade, Keene and Sackett (1981) examined how Americans’ support for trade restrictions against Japan was affected by their standing on a “mushiness index” measuring how genuine their attitudes were. Respondents with the least genuine attitudes were uncertain, and evenly divided in their preferences. Conversely, respondents with genuine attitudes strongly favored trade restrictions, and rarely expressed uncertainty. Despite this “conventional wisdom” about uncertainty, few contemporary surveys about policy attempt to ascertain if opinions are genuine, raising the specter that non-attitudes may be distorting our understanding of the public’s policy preferences.

Data and Methods

Our data come from a unique opinion survey of North Carolina that we conducted in October of 2010, right before the midterm elections. If Americans have meaningful opinions about trade, we should find them around an election period in a state like North Carolina, where the textile and furniture making industries have been especially hit hard by free trade policies; some 380,000 manufacturing jobs have been lost since the implementation of NAFTA. Our survey of 663 adults was conducted over the internet by Knowledge Networks. It has a margin of sampling error for the sample as a whole of 3.6%, a completion rate of 70%, and a response rate of 21% using AAPOR standard definition 3.

We measured respondents’ support for free trade by asking respondents: (1) “Do you favor or oppose United States’ efforts to promote free trade globally” and (2) “Do you favor or oppose the United States participating in more regional free trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)”? In this article, we limit our analyses to the second question about trade agreements because the results are mostly redundant.

Prior to measuring their issue preferences, however, we asked respondents two questions that pollsters could use to weed out respondents with non-attitudes: (1) how much they thought about trade policies and (2) how important the issue of trade was to them. Yet, instead of weeding out respondents who did not think about trade or find it important, we use their responses to demarcate non-attitudes and then compare preferences between those who likely have and do not have genuine attitudes.

Secondly, also in contrast to most survey research about trade, we designed respondents’ answer options so that those with non-attitudes initially would not be forced to pick a directional issue position. Prior research shows that respondents lacking important attitudes about an issue are prone towards choosing a middle answer option (Bishop 1987; Krosnick and Schuman 1998). Thus, our strategy allows respondents to initially express feeling “neutral” about trade. Only after selecting the “neutral” answer option were respondents prodded into reporting a directional issue position, mostly to investigate how they would react.

Thirdly, we also measured the intensity of respondents’ preferences by asking respondents who initially expressed one if they held their opinion “strongly” or “not strongly”, and we report these distributions where appropriate. As Moore (2011) points out, attitude intensity is only sporadically measured, and studies show that more strongly held opinions are more stable over time; and therefore they provide an additional indicator of more meaningful attitudes (Krosnick and Smith 1994).

Lastly, it is worth noting that we did not provide respondents with the explicit answer option of “no opinion”. While we agree that providing this answer option can be valuable to weed out those with no opinions, we have already included measures to identify non-attitudes, plus there is some debate about whether meaningful opinions are inadvertently discarded as a result (Krosnick et al. 2002). In addition, Knowledge Networks recommends against providing an explicit “no opinion” choice because of internet mode effects.

The Prevalence of Non-Attitudes

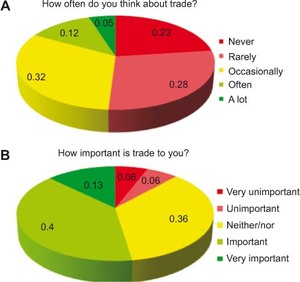

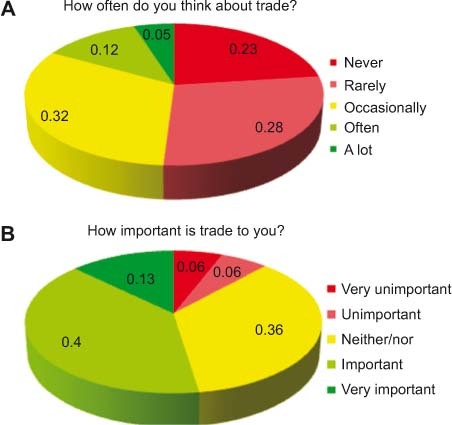

We start by presenting results for the two questions used to screen for non-attitudes. These findings can be found in Figures 1a and 1b. Despite the presumed topical nature of trade in North Carolina, most respondents admitted to not thinking much about it. In fact, just 17% combined said they thought about free trade “often” or “a lot”. By way of comparison, about a quarter of respondents answered that they “never” thought about trade. In total, over half (51%) of the sample said they “rarely”, or “never” thought about trade.

Our question about issue importance produces comparable results. While a slim majority (52%) said trade was at least “important” to them, only 13% said trade was “very important”. Turned around, this means about half of the sample (48%) said they were indifferent about trade or they found it unimportant. In combination, the results from these two questions indicates a sizeable proportion of the sample is unlikely to have meaningful opinions about trade, because they don’t think much about it and rate its importance as middling.

Preferring the Mid-Point

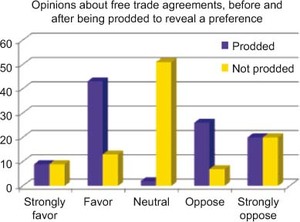

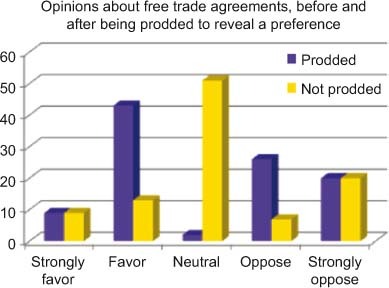

What percentage of respondents initially avoids taking a directional issue position about free trade agreements, instead choosing the “neutral” answer option? How does prodding the respondent to answer affect the distributions of reported opinions? In Figure 2, we present the distribution of respondents’ opinions before and after being prodded.

Most people (51%) initially answer the question by saying they feel neutral about trade agreements. Given the large percentages of respondents admitting to not thinking about trade or finding it important, this result is unsurprising but important. Of course, sometimes respondents are genuinely conflicted or ambivalent on an issue, and the midpoint is therefore attractive to them. As we report in greater detail below, however, attitude complexity is unlikely to account for the high percentage of neutral answers since most respondents who prefer the scale midpoint don’t think about trade.

In addition, roughly equal percentages of those initially expressing a preference support and oppose trade, although opposition is a bit more prevalent and definitely more intensely held. Prodding respondents into taking a position, however, dramatically changes our depiction of public opinion on this issue. Only after prodding does a majority of respondents report favoring trade agreements, and the directional preference of the majority is contrary to plurality opinion before prodding. It appears as though majority support is the artificial result of pushing people, many with non-attitudes, to answer the question.

Fictitious Majority Support for Trade

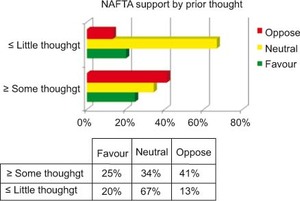

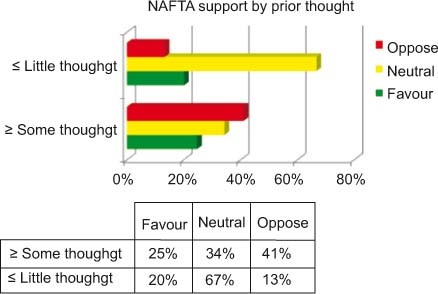

We extend this line of inquiry by examining more closely how thinking about trade is related to opinions about it (we skip reporting the results for issue importance because they duplicate our findings for thinking). These results are displayed in Figure 3.

Most respondents who don’t think about trade also initially answered feeling neutral about it. For those who “never” thought about it, about three-quarters of them do not choose a directional preference. Likewise, a few more take a side among those who rarely think about, but over 60% still fail to do so.

More to the point, supporters of trade outnumber its opponents among those who do not think much about it (rarely or never), but opponents outnumber supporters by about 2-1 among the group more likely to have genuine opinions about it (respondents who say they think about trade “often” or “a lot”). If we had used the thinking question to filter out non-attitudes by not asking some respondents about trade rather than investigating how non-attitudes correlated with preferences, we would have arrived at a very different portrait of public opinion. Instead of describing supporters of trade as being in the majority, by prodding and not screening, we would instead be writing about an intensely opposed plurality (or majority).

Voting Correctly?

We complete our empirical analysis by showing how accounting for likely non-attitudes affects estimates of whether voters can pick candidates “correctly”. Do opponents of trade, for example, also plan to vote for a candidate opposed to trade? In the 2010 elections for US Senate in North Carolina, the two main candidates offered stark policy alternatives about free trade. Elaine Marshall, the Democrat, openly opposed free trade policies while Richard Burr, the Republican, had voted in favor of prior trade agreements and described himself as a proponent of free trade policies.

We simplify our task by comparing respondents’ intention to vote for Burr, the free-trade candidate, by their trade preference (reduced to support/oppose) and whether they think much about it (rarely and never versus occasionally or more). The data for this part of our analysis come from before prodding respondents into taking a position.

As we show in Table 1, whether citizens can “vote correctly” depends on whether or not we control for non-attitudes, defined as the difference between thinking and not thinking about trade.

Looking first at those who opposed trade agreements, most respondents voted “incorrectly” by picking Burr. However, while an astounding 80% of trade opponents who did not think about it planned on voting for Burr, the percentage of “incorrect” voting drops to 61% among those who think more about trade.

Likewise, proponents of trade also planned on voting for the wrong person (Marshall) if they didn’t think about the issue; just 34% of these respondents planned on voting for Burr. The voting calculations of trade’s supporters, however, are mostly “correct” if they reported thinking more about trade. Within this group, 61% of them said they were (“correctly”) voting for Burr.

As a final check on our suspicion that the mid-point captures non-attitudes about trade, we looked at the voting preferences of respondents who had to be prodded into taking a position (not presented in tabular form). A majority of these respondents planned to vote “incorrectly” regardless of whether they thought much about trade (which few of them did, of course). Most respondents leaning against trade agreements preferred Burr, and almost 7 in 10 respondents leaning in favor of trade agreements supported Marshall.

Implications and Conclusions

Our findings have a number of important implications. First, our results provide support for critics like Moore (2008, 2011) who contend that common polling practices manufacture majorities in public opinion. Most basically, non-attitudes on trade are surprisingly rampant in North Carolina. More seriously, their inclusion affects our understanding of public opinion about trade. Most disconcerting is the possibility that representatives’ policy choices are guided by following a dubiously created majority sentiment.

In addition, our results can help explain the misleading impression that voters are fools. It only appears at first glance that people vote against their own interests when it comes to trade policy because in reality many of them aren’t voting on the issue of trade at all—a majority, perhaps, simply doesn’t care enough about the issue. When we examine the voting choices of those who think about the issue, for example, we find that these respondents are likely to vote “more correctly”, a point that would normally go unnoticed.

Thirdly, they suggest that scholarly debates about the drivers of public opinion regarding trade are based on questionable data. Our review of the literature finds survey respondents are almost never screened for non-attitudes and rarely are they given the option of answering that they do not have an opinion. At a minimum, the inclusion of weak to non-existent preferences reduces the precision of our analyses. They can also distort our estimates of the correlates of support for trade if respondents who have no real thoughts about trade policy answer questions about it more favorably because of cues in the question wording (e.g., Best and McDermott 2007).

Of course, there are limitations to our data, and we could have experimentally varied the measurement practices to more carefully compare how they matter. If the goal is to evaluate whether standard survey practices detract from the utility of policy polling, however, these results surely indicate cause for concern.

Authors’ Note

We are indebted to the School of Public and International Affairs at North Carolina State University for the generous funding and assistance in the development and administration of the 2010 North Carolina Voter Survey, including research assistance used in this article provided by Arne Plum.