Introduction

Given the trend to rely on mobile devices to conduct a wide variety of activities online (e.g., social networking, navigation; Nielsen 2013), it is not surprising that the proportion of online surveys completed through a smartphone has also increased (Olmsted-Hawala et al. 2018; Sonck and Ferine 2014). This fact has not been lost in the survey design literature, which has proposed different guidelines for effective design of surveys on mobile devices (for a review, see Antoun et al. 2017). The trend to rely on a mobile device to go online is present for populations of all ages (Pew Research Center 2019). However, older populations are likely to encounter cognitive and physical challenges when interacting with a smartphone (Johnson and Finn 2017). Because of this, special attention is required in the design of mobile surveys to maximize survey completion and satisfaction of all populations.

Previous studies have included older adults to determine the survey characteristics that would promote effective and efficient survey completion for everyone (Antoun et al. 2020; Falcone et al. 2020; Olmsted-Hawala et al. 2018). For example, Nichols et al. (2020) found that, when completing surveys on a smartphone, the difference in time spent on task between younger and older adults is larger when the task requires users to touch/interact with the keyboard. Similarly, Leung, McGrenere, and Graf (2011) found that, compared to younger adults, older adults are less likely to correctly interpret an icon’s meaning when the icon image lacks similarity to the real-world object or functionality that it is supposed to portray. Two characteristics of mobile surveys that are yet to be explored in an older population include the placement and format of navigation buttons.

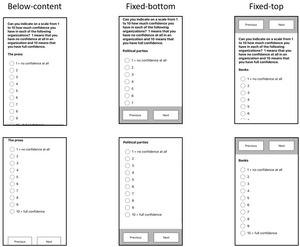

Navigation buttons allow Web users to go to the previous page or move forward to the next page. They can be labeled with either text (e.g., “back” or “previous” and “next”) or symbols (e.g., “<” and “>”). The conventional design places navigations buttons below the content on a Web page (Couper, Baker, and Mechling 2011; Romano Bergstrom, Lakhe, and Erdman 2016). For the remainder of this paper, we refer to this format as “below-content.” As shown in Figure 1, if a Web page is longer than a smartphone screen, the navigation buttons may not be visible (Figure 1, panel A) until the page is scrolled down to the bottom (Figure 1, panel B).

One advantage of the “below-content” design is that it maximizes screen usage because the navigation buttons appear only at the bottom of the content. Another advantage is that it forces respondents to scroll through all possible response choices in a survey. One possible drawback is that scrolling on a smartphone screen requires fine motor control. This may present a challenge for older adults and reduce the satisfaction with which this population completes a survey on a smartphone.

Two alternatives to the “below-content” design include having the navigation buttons fixed (ever present) at the top or bottom of the screen. In such designs, navigation buttons would be always visible, and navigation to other survey pages without scrolling would be possible. The user then could preview the survey pages quickly by tapping in the same location repeatably, and it allows the users to easily return to a previous page to make a correction.

One concern with the fixed navigation button design is that, when not all response choices are visible, respondents may only select visible response choices without scrolling. This behavior of choosing what is visible has been observed with dropdown designs that require scrolling (Couper et al. 2004), and it is problematic because it can potentially compromise the accuracy of responses.

In the present study, we examined the effect of format of navigation buttons on data quality, and the efficiency and satisfaction with which older adults complete surveys in a smartphone. We hypothesize that

Hypothesis 1: Respondents will complete a survey faster in conditions with fixed navigation buttons compared to when navigation buttons are presented at the bottom of the content.

Hypothesis 2: Respondents will be more likely to select a response choice that is initially visible (visible without the need to scroll) when completing a survey with fixed navigation buttons, compared to completing a survey with navigation buttons at the bottom of the content.

Hypothesis 3A: If hypothesis 1 is supported, respondents will be more likely to rate the surveys with fixed navigation buttons as easier to complete than surveys with navigation buttons below the content.

Hypothesis 3B: If hypothesis 1 is supported, respondents will be more likely to rate the surveys with fixed navigation buttons as easier to navigate than surveys with navigation buttons below the content.

Hypothesis 3C: If hypothesis 1 is supported, respondents will be more likely to prefer a fixed navigation format than the navigation format where buttons are below the content.

Methods

Participants

Sixty-two individuals aged 56–78 years (mean age = 70.3, SD = 4.7; median age: 70.4; 19 males and 43 females) participated in this study between January and March 2018. All participants were recruited in two senior centers in the Washington D.C. metro area. The experimental session took place in a room that was provided by the senior center personnel and was furnished with tables and chairs. The participants were seen one at a time by one researcher. All participants, except two, reported having obtained a high school diploma or higher. For time of experience using a smartphone, 10% of the sample reported between six months and one year, 15% of the sample reported more than one year but less than two years; and 75% of the sample reported having two or more years of experience. All participants were fluent in English and had normal habitual vision. (The vision one usually has in daily living, with or without glasses.) Prior to participating in the study, all participants provided written informed consent. Participants were given a small honorarium upon completion of the study.

Experimental Design

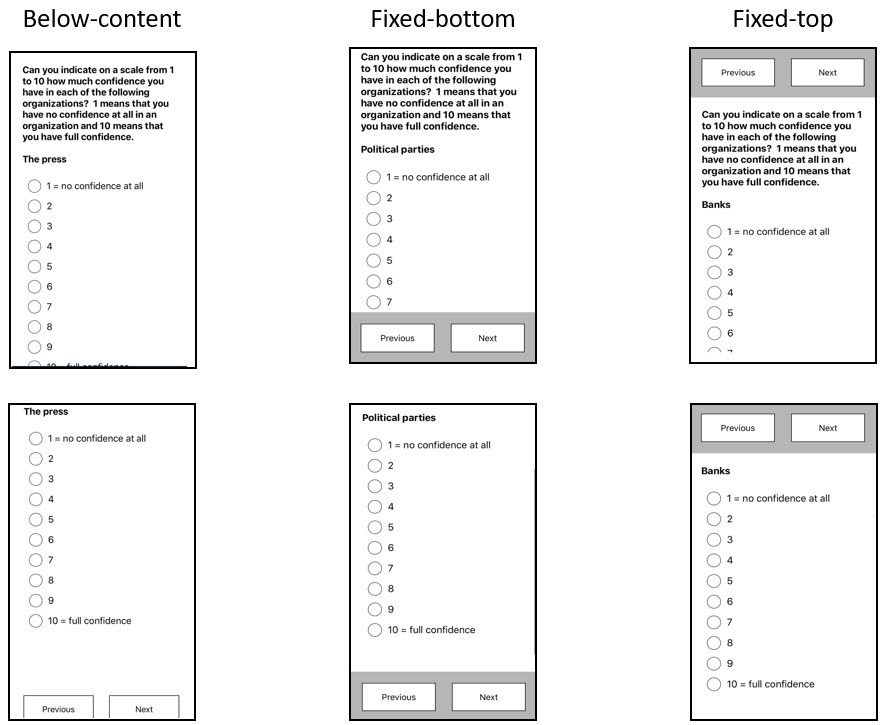

The experiment was a within-subjects design. The experimental factor (format of navigation buttons) included three conditions: (1) Below-content: This is the conventional design where navigation buttons are placed below the page content. Navigation buttons appear or disappear when the respondent scrolls up and down; (2) Fixed-bottom: navigation buttons are fixed (ever-present) at the bottom of the screen and remain visible when the respondent scrolls up or down; (3) Fixed-top: navigation buttons are ever-present at the top of the screen and buttons are always visible when the respondent scrolls up or down. A visualization of the three experimental conditions is presented in Figure 2.

Procedure

Participants completed three nine-question surveys on a smartphone provided by the researchers (iPhone 5). Each survey included one of the three different experimental conditions. The order of the three surveys were counterbalanced across participants. All surveys had one question per page, and participants had to answer each question prior to moving forward. Each survey included nine questions. Three of the questions included five response choices, and six questions included ten response choices. Two questions in each survey (the 3rd and 8th questions) needed scrolling to see all the answer choices. This is because these questions were presented with instructions, which occupied about one third of the screen. This caused some of the response choices to require scrolling to be visible. The remaining items did not include the presentation of instructions. This liberated screen space and allowed all the response choices to be visible without scrolling. The specific wording and response options for all surveys can be found in Appendix A. After each survey, participants rated their perceived difficulty of completion and difficulty of navigation. After completing all the surveys and difficulty ratings, participants were presented with the three designs of navigation buttons placement side by side and were asked to select their preferred design.

Performance Measures

We measured the completion time, response distribution, and satisfaction with which participants completed each of the surveys under the different experimental conditions. Completion time was operationalized as the amount of time (in seconds) that it took the participant to complete a survey from selection of the “Begin Survey” button at the start of the survey to selection of “Submit Survey” button at the end of the last survey. Response distribution was operationalized as the proportion of the sample that selected each of the different answer choices for the items in the survey. Satisfaction was recorded by three different measures: completion difficulty, navigation difficulty, and preference. Completion difficulty was operationalized as the participant’s response to the question “How easy or difficult was it to complete this survey?” Navigation difficulty was operationalized as participants’ response to the question “After answering a survey question, how easy or difficult was it to move to the next question?” Response choices to the completion difficulty and navigation difficulty questions included a 5-point Likert scale (1= “Very easy” and 5= “Very difficult”). Preference was recorded as binary outcome of participant’s selection of preferred navigation placement among the three designs.

Data Analyses

Inferential statistical analyses were conducted to compare completion time, response distribution, completion difficulty, navigation difficulty, and preference among the three experimental conditions (below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top). An alpha level of .05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance and all modeling accounted for the repeated measures design.

Results

Survey Completion Time

Completion time was recorded in each condition for the 62 participants. After removing one outlier (+3 SD above the mean) in each of the experimental conditions, Shapiro tests indicated that the distributions of completion time were significantly different from normal (p < .001 for each of the three conditions). After subjecting the completion time data to a log transformation, Shapiro tests indicated that the distributions of log-transformed completion time in the three experimental conditions conformed to normality (Below-content: p = .06; fixed-bottom: p = .08; fixed-top: p = .08). Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for completion time.

In order to assess the effect of navigation button placement on survey completion time and test Hypothesis 1, the log-transformed completion time data were entered into a univariate repeated measures ANOVA with three levels: Below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top. The results of this analysis indicated a statistically significant effect of navigation button placement (F(2, 122) = 4.62, p < .001).

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that the log-transformed completion time was shorter in the fixed-bottom condition than in the Below-content condition (Mean Difference = .08, 95% CI [.03 - .14], t(61) = 2.89, p = .005, d = 0.36). No other comparisons were statistically significant. These results partially support Hypothesis 1.

Response Distribution

To test Hypothesis 2, we modeled the answer choices using a mixed model for ordinal data using the cumulative logit model. This analysis was limited to the two questions where the respondent had to scroll to see all the response choices. Answer choices for these two questions ranged from 1 to 10. Lower numbered choices were visible (e.g., the response choice 1 was always visible) more so than higher numbered choices (e.g., the response choice 10 was never visible without scrolling). Due to 5 missing answers, only 367 observations were used (62 participants * 3 questionnaires * 2 long scrolling questions = 372). The distribution of response selection across the different conditions is presented in Table 2.

The predictor of interest was the navigation button placement (below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top). Included in the model was a fixed effect for the questionnaire and question and a random effect on the intercept for the participant. Results indicated that participants were more likely to choose a lower numbered answer in the fixed-bottom condition (β=.5, SE=.2; t=2.3, p=.02) and in the fixed-top condition (β=.6, SE=.2; t=2.5, p=.01) compared to the bottom-content condition. The results of this analysis provide support for Hypothesis 2.

Completion Difficulty

Data on perceived completion difficulty were recorded from each of the 62 participants. The distributions of completion difficulty rating can be found in Table 3.

Ratings on completion difficulty were entered into a generalized estimating equations (GEE) to fit a repeated measures logistic regression, with difficulty (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, where higher values indicate higher difficulty) as the predicted outcome and the three levels of navigation button placement (below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top) as predictors. There was an effect of navigation button placement on completion difficulty: Compared to the below-content condition, participants were more likely to rate the fixed-top condition as more difficult to complete the survey: b = .23 (.06), 95% CI [.11, .36], p = .0003. No other differences were statistically significant (p > .05). The results of this analysis do not provide support for Hypothesis 3A.

Navigation Difficulty

Data on perceived navigation difficulty were recorded from each of the 62 participants. The distributions of navigation difficulty rating can be found in Table 4.

Ratings on navigation difficulty were entered into a generalized estimating equations (GEE) to fit a repeated measures logistic regression, with difficulty (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, where higher values indicate higher difficulty) as the predicted outcome and the three levels of navigation button placement (below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top) as predictors. This analysis indicated no effect of navigation button placement on navigation difficulty rating (p > .05). The results of this analysis do not provide support for Hypothesis 3B.

Design Preference

Due to technical reasons, two data points were missing. Thus, data on preference among three formats of navigation button were collected from 60 participants. Table 5 provides the frequencies for the preference outcome.

In order to explore preference distribution, preference data were entered into a goodness-of-fit test. This analysis indicated that the proportions of the preferred design selection was different than chance: (χ2(2) = 22.8, p < .001). Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that a larger proportion of the sample preferred the below-content condition than both the fixed-bottom (z = 2.45, p < .001) and the fixed-top condition (z = 4.63, p < .001). The proportion of the sample that preferred the fixed-bottom was larger than the fixed-top condition (z = 2.45, p < .001). The results of this analysis do not provide support for Hypothesis 3C.

Discussion

The present study explored the effect of three different formats of navigation button (below-content, fixed-bottom, and fixed-top) on completion time, response distribution, and satisfaction with which older adults complete a survey on a mobile device. We found that participants complete a survey faster in the fixed-bottom condition than in the below-content condition, meaning that the fixed-bottom alternative is more efficient than the current conventional format (below-content). We also found that participants are more likely to select visible response choices in the fixed-bottom and fixed-top conditions than in the below-content condition, indicating that the conventional design (below-content) may be a better alternative for participants to see all the possible choices before selecting a response. We also found that participants perceived the fixed-top condition as more difficult to complete than the below-content condition, and that most participants selected the below-content condition as their preferred format of navigation buttons.

The finding that survey completion is faster with navigation buttons ever present at the bottom of the screen is in line with Buskirk and Andres’ (2012) recommendation that navigation buttons be visible to reduce time and burden associated with scrolling. However, it is possible that this increase in efficiency is due to participants selecting visible response choice to avoid scrolling before navigating to the next survey question. This is problematic because it may mean that the fixing of the navigation buttons at the bottom of the screen may promote faster completion time at the expense of data quality. Given these findings and the potential data quality issues found in the fixed conditions, we recommend that mobile surveys include navigation buttons at the bottom of the survey content.

The finding that the most efficient design (fixed-bottom) was not perceived as the easiest, nor was it selected as the preferred format, is worthy to note. The surveys completed under the different conditions in this study were relatively short (9 questions per survey). It is possible that, for longer surveys, the time saving provided by the fixed-bottom condition may be more evident for participants. This, in turn, may influence the selection of preferred placement. Future studies that include longer surveys in the experimental task and a sample with a wider age range could provide further insights regarding the effect of format of navigation buttons, satisfaction with which older adults complete surveys on a mobile device, and whether these preferences differ across age groups.

Disclaimer

This report is released to inform interested parties of research and to encourage discussion. The views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the U.S. Census Bureau. The paper has been reviewed for disclosure avoidance and approved under CBDRB-FY21-CBSM002-028.