The potential consequences of question wording effects—including effects tied to how a topic is framed—are well-documented (e.g., Schuman and Presser 1996). In the political domain, seemingly trivial differences in how a policy is described—e.g., “climate change” versus “global warming” (Schuldt, Konrath, and Schwarz 2011) or whether a question references “aid to poor” or “welfare” (Rasinski 1989; Smith 1987)—can substantially affect the political attitudes survey respondents report. Scholars posit that question wording effects manifest because how a question is phrased or framed can affect which “considerations” come to a respondent’s mind as they construct their response (e.g., Zaller and Feldman 1992).[1] This framework points to an expectation that differences in how a question is framed are likely to be particularly consequential on low salience issues where respondents have few existing considerations to draw on. In these circumstances, responses may be heavily influenced by considerations cued by the way a question is posed.

We report findings from an issue framing experiment (Busby et al. 2018) fielded using a sample of residents of Cook County (home to Chicago) that varied the stated purpose of a set of policies often found in municipal “welcoming ordinances.” The provisions we presented to respondents each forbid police from proactively enforcing federal immigration law. The treatment conditions framed the issue in starkly different ways: one highlighted the potential for these policies to improve undocumented immigrants’ willingness to cooperate with the police; the other appealed to the symbolic importance of inclusivity. Thus, the experiment went well beyond differences between “climate change” and “global warming” or “aid to poor” and “welfare.” The treatments presented respondents with explicit considerations relevant to an important, but novel and low salience, policy that few respondents had likely given much thought to.

Absent an explicit cue, some respondents might readily assume that these policies are driven by an interest in promoting diversity, inclusivity, and “welcoming-ness.” However, we suspect few had considered the potential for these policies—which, on their surface, appear to tie the hands of law enforcement officers—to aid law enforcement. Thus, we suspect the treatments (especially the law enforcement treatment) provided respondents with new “considerations” to weigh in formulating their opinion. Beyond this, there would seem to be ample reason to expect the rationales presented in the treatments to vary in terms of their appeal to different subgroups.

However, the treatments did not significantly affect overall support for the policies relative to a control where no justification for the policies was offered, nor did they affect support among subgroups where we might expect to find particularly strong effects. Documenting these findings is important given the “file drawer problem” where studies that yield null results are less likely to published (e.g., Franco, Malhotra, and Simonovits 2014). Our findings also contribute to a growing body of literature that demonstrates the limits of framing effects (Bechtel et al. 2015; Druckman 2001).

Design and Analysis

We fielded our online survey in English in February 2022 using an online panel of respondents from Dynata. The target population was adult residents of Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago and its immediate suburbs. Of the 2,358 respondents who initiated the survey via Dynata, 1,530 were marked as completing the survey. We exclude 86 respondents who did not provide usable responses to the items we analyze below (including 35 who declined to agree to the consent form at the start of the survey) for an overall N of 1,444 (summary statistics are reported in Table A.1). The battery of questions we focus on here asked respondents to rate their support for each of three provisions—adapted from Chicago’s “welcoming ordinance”—on a five-point scale. The provisions would (1) forbid police and other officials from asking residents about their immigration status, (2) forbid police from making an arrest solely on the basis of suspicions regarding immigration status, and (3) forbid police from using time/resources to help federal agents with immigration enforcement.

The questions were preceded by text that randomly varied the purported purpose of the provisions, drawing on two justifications that we expected to affect attitudes relative to a condition where no justification was provided. We also expected them to differ in their appeal to particular subgroups of respondents. The purpose of the policies was described either as “to encourage immigrant communities to cooperate with law enforcement” or “to show their commitment to inclusivity for people from all parts of the world.” No justification was offered in the third (control) condition. Full question wording is presented in the Appendix.

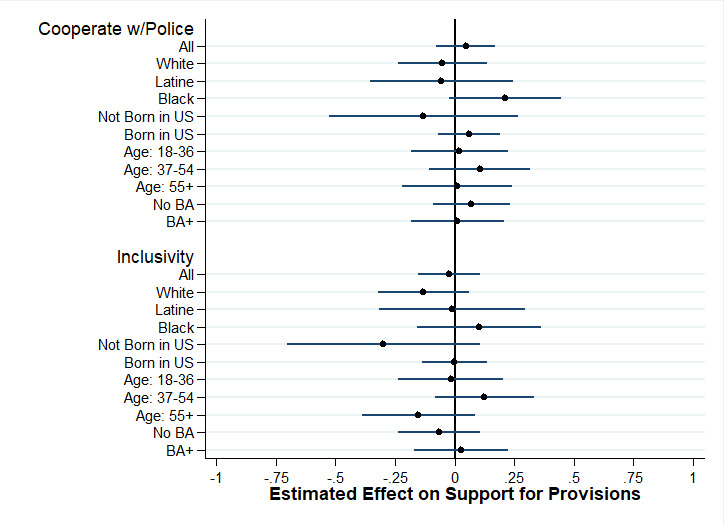

For our analysis, we standardized responses to the three policy support questions and combined them into an index with a mean of zero and standard deviation of 1 (Cronbach’s alpha = .902). We report our first set of estimated treatment effects in Figure 1. The top portion of the figure reports the effect of the “cooperate with police” frame relative to the control condition; the bottom portion reports the estimated effect of the “inclusivity” treatment. The first marker in each set of estimates pools all respondents. The point estimates associated with the “cooperate with police” and “inclusivity” treatments are each trivial and fall well short of conventional thresholds of statistical significance (B = .046, p = .466 and B = −.023, p = .732, respectively). The regression models used to generate these estimates and a similar model controlling for respondent demographics are reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table A.2. Power calculations indicate that, specifying a power level of .8, a design like ours (with almost 500 cases per experimental condition) is positioned to reliably identify effect sizes of about one-tenth of a standard deviation. The standard errors on our treatment indicators (approximately .06) tell a similar story: we should be able to identify direct effects as small as one-eighth of a standard deviation.

The remaining markers in Figure 1 consider the possibility that the treatment effects varied across demographic groups who we might expect to differ in the extent to which they find appeals to inclusivity or cooperation with law enforcement to be attractive. For example, young participants in the American National Election Studies 2020 Exploratory Testing Survey were significantly more likely to say that “increasing the number of people of many different races and ethnic groups in the United States” makes the country “a better place to live” and that police officers often “use more force than is necessary” than older participants. However, none of the 20 estimated treatment effects reach conventional thresholds of statistical significance. Furthermore, tests of the equality of the coefficients on the two treatments fell short of conventional thresholds of statistical significance for all groups (p > .10 for all treatment effect comparisons).

In Figure 2, we consider subgroups defined by their attitudes and political identities. We focus on items measuring respondents party identification,[2] how safe respondents feel in their neighborhood, and whether they view crime as a problem in their neighborhood. We expected Republicans to respond particularly favorably to justifications regarding cooperation with police and, perhaps to be averse to a policy that would seem to “soften” immigration enforcement in the name of “inclusivity.” In contrast, we expected Democrats to respond more favorably to appeals to “inclusivity.” Similarly, we might expect those who are particularly concerned about their safety or crime rates in their area to respond particularly favorably when the potential for these policies to encourage cooperation with law enforcement was emphasized.

Although Republicans were significantly, and substantially, less supportive of these policies overall (Republicans scored almost a full standard deviation lower than Democrats on our outcome measure; also see column [3] of Table A.2), their attitudes were not significantly affected by the treatments. We find, at most, meagre evidence that describing the purpose of the policies as promoting “inclusivity,” reduced support among this group. The point estimate is modest (approximately .2 standard deviations) and is not statistically distinguishable from either the control condition (p = .183) or “cooperate with police” condition (p = .128).[3] Democrats were similarly unmoved by the treatments.

Figure 2 also offers little support for our expectation that treatment effects would vary with respondents’ answers to a question asking, “How safe do you feel in your neighborhood?” or a question asking, “How much of a problem is crime in your neighborhood?” The estimated effect of each treatment (relative to the control condition) is trivial in size and null across all groups. Additionally, in no case is the difference in support across these two treatment groups statistically significant (p > .10 for all comparisons).[4]

It is important to note that our statistical power is lower in our subgroup analysis. The standard errors associated with the treatment estimates reported in Figures 1 and 2 indicate that our design should allow us to identify effects ranging from about .15 standard deviations for larger subgroups (e.g., Democrats in this urban sample) to about two-fifths of a standard deviation for smaller subgroups (e.g., respondents who reported not being born in the United States). However, the point estimates reported in Figures 1 and 2 suggest that this is not a situation where substantial treatment effects are simply failing to reach conventional thresholds for statistical significance. The 60 estimates (including pairwise comparisons to the control condition and comparisons between the treatments) range from -.30 to .23, with a mean of .03 and standard deviation of .11, and are approximately normally distributed (see Figure 3). Overall, the distribution of estimated treatment effects is essentially what we would expect to find by chance in a world where the treatments did not affect attitudes among any group. Putting aside conventional thresholds for statistical significance, the patterns of estimates fail to conform to any theoretically coherent framework.

Discussion

Why did we find so little evidence that variation in how the purpose of these local policies were framed affected support? One possibility is that respondents simply were not paying attention to the questions we focus on. The strong relationship between party identification and reported attitudes casts doubt on this explanation. Additionally, we estimated a model interacting a logged measure of total time respondents spent on the survey with the treatment indicators and find little evidence that those who spent longer on the survey were more responsive to the treatments (p = .523 and .521 for coefficients on the interaction terms).

Another possibility is that views on these policies are rooted in potent intergroup attitudes or dispositions regarding authority, which may make them less subject to framing effects (Bechtel et al. 2015; Lecheler, de Vreese, and Slothuus 2009). However, as discussed above, there is also reason to expect attitudes about these policies to be particularly susceptible to framing effects. Although debates about so called “sanctuary cities” receive periodic news coverage, we suspect that few people have reflected carefully on arguments for or against these policies. Having fewer “considerations” to draw on would seem to create ripe ground for framing effects to emerge. Investigating the conditions under which framing effects emerge is an important and ongoing project that is beyond the scope of this report. Here we simply document that efforts to frame a policy by emphasizing a particular goal of the policy do not always meaningfully affect the public’s attitudes.

This said, our findings offer some guidance for practitioners. There is reason to be concerned that the (correct) notion that small changes in question wording can lead to dramatic changes in patterns of response to survey questions has evolved to a perception that changes in question wording always lead to dramatic changes in patterns of response. This perception may be unduly reinforced by a tendency for studies that identify statistically significant question wording effects to be over-represented in both public reporting and scholarly work. If studies where no question wording effects emerge remain in the “file drawer,” practitioners evaluating work produced by other scholars and survey professionals—or their own work—may worry more about the consequences of minor changes in question wording than is warranted. Similarly, if journalists and others who report on polls highlight instances where question wording is consequential but fail to note cases where public attitudes are insensitive to variation in question wording, the public may lose faith in the ability of surveys to facilitate effective self-governance. In short, our findings suggest that practitioners and consumers of polling data should be attentive to when question wording effects emerge and resist the temptation to assume that such effects are substantial and pervasive.