1. Introduction

While probability-based panels dedicated to social research are operating now in many countries (Blom et al. 2016), the daily management of such panels leaves open many questions about how to best allocate the resources dedicated to these infrastructures to offer an optimal quality of service. In the survey tradition, service is largely defined by the internal and external validity of panel data, which depends on several factors including the quality of the sample. Much has been said on the impact of the initial recruitments in probability-based panels; attrition has also received a lot of attention (Clinton 2001; Lynn et al. 2005; Das, Toepoel, and van Soest 2011; Genoni et al. 2021). Less insights have been proposed into what happens in between, i.e., the participation of panellists in each of the specific waves.

Panellists’ propensity to respond to a specific study in a panel varies across individuals (Behr, Bellgardt, and Rendtel 2005; Fitzgerald, Gottschalk, and Moffitt 1998; Voorpostel and Lipps 2011; Lugtig, Das, and Scherpenzeel 2014; Voorpostel 2010). For instance, there are groups of almost perfectly reliable and reactive panellists who respond systematically; there are also those who are likely to drop out early, and different patterns of more or less erratic behavior (Lugtig 2014). Most of the time, nonparticipation and, eventually, attrition result from conscious decision-making from panellists. Among different psychosociological factors involved in this process, commitment to the panel study is crucial. For instance, the fact that the participation in the previous wave of a panel predicts best the participation in the next wave reflects the effect of commitment. One can consider various mental processes underlying it, such as self-identification, social pressure, or habit. Whatever these mechanisms are, commitment is important for online panels that are found to be more subject to attrition than offline panels. Online panels usually solicit their participants more often to respond to surveys (Lugtig, Das, and Scherpenzeel 2014), and the absence of interviewers makes the relationship between the panel and the panellist impersonal. Thus, a systematic telephone callback of nonrespondents by panel managing staff seems to be vital for maintaining satisfactory response rates in online panels (Blom, Gathmann, and Krieger 2015; Roscoe, Lang, and Sheth 1975).

Such an approach being time- and energy-consuming, insights about best practices seem to be particularly valuable. Many decisions pertaining to setting up an efficient telephone callback protocol are constrained by the availability of financial resources (and therefore staff) and the panel management agenda. The experimental protocol exposed in the present paper had two aims: testing the effectiveness of a telephone callback protocol and examining what profiles of the panellists are the most receptive to telephone callbacks in a noncommercial online survey panel. In doing so, we focused especially on the measures reflecting the panellists’ commitment.

However, as evidenced by existing literature, there are many streams of nonparticipation. Bad health (Goldberg et al. 2001), low level of education (Alderman et al. 2001), poor economic status (Burkam and Lee 1998; McCurdy, Mroz, and Gritz 1998; Russell 2002), and weak cognitive capacities (Botwinick and Siegler 1980) seem to be correlated with the probability of attrition. Moreover, gender differences also seem to be related to this phenomenon, insofar as females tend to be less prone to attrition than males, although this seems to be controversial (Behr, Bellgardt, and Rendtel 2005; Lepkowski and Cooper 2002; Uhrig 2008). Finally, extreme age categories, especially the eldest, would be more prone to attrition (Genoni et al. 2021; Hayslip, McCoy-Roberts, and Pavur 1999; Voorpostel and Lipps 2011). Conversely, Goodman and Blum (1996) found that married, elderly, and educated Caucasians were particularly likely to stay in the panel in the long run. Therefore, in the experimental setup exposed in this paper, we controlled either for these exact characteristics, or at least for their proxies.

2. Methods

This study is based on a French panel Longitudinal Internet Studies for Social Sciences (ELIPSS). Based on random sampling in census or fiscal data, it is representative of the adult population (over 18) living in France. It was established in 2012 and then refreshed twice (in 2016 and 2020). The initial recruitment in 2012 (27% of the sampled individuals) and 2020 (14%) each used a slightly different mix of recruitment strategies (postal mail, email, telephone, website, face-to-face, and an occasional use of 10€-voucher incentives), whereas 2016 recruitment (32%) was solely face-to-face with a telephone follow-up.

ELIPSS is dedicated exclusively to research in social sciences, and “interest in research” is one of the motives for joining the panel that are the most often mentioned by its new panellists on the occasion of the introductory survey. Moreover, the image of the panel as a research facility benefits from the reputation of its parent institutions: Sciences Po and French National Centre for Scientific Research. The panellists are solicited once per month to respond to a study that needs on average about 20 minutes to fill in. Topics covered by the studies are very diversified (politics, arts, leisure activities, social subjects, etc.). In addition, every year, a specific survey refreshes all the profile information on the panel respondents. Special open-ended items are included in each questionnaire to let the respondents give feedback about their impressions and difficulties.

Appropriate care is taken to inform the panellists about their rights resulting from the General Data Protection Regulation and to provide necessary assistance if needed. For that purpose, they have the possibility to contact panel management staff by email or by telephone (normal call charges, available five days a week). Each year, at back-to-school time and at the end of year, wishes are sent to the panellists by postal mail together with a small sum (10€) voucher. There was a 21.4% attrition of the original panel at the moment of the refreshment in 2016; the attrition of the panellists recruited in 2016 reached 60.6% in 2020.

Until 2019, every ELIPSS panellist was equipped with a tablet with a dedicated application installed, and a 4G internet connection to respond to studies administered to the panel. This measure was discontinued afterward. Since then, ELIPSS panellists have responded to surveys using their own devices. If necessary, panel managers provided telephone assistance for opening contact email accounts and/or finding internet access in the vicinity of the panellist’s place of living (for example, in a library). The panellists could access the questionnaires by following links integrated in invitations sent by emails. Those who have not responded have been systematically reminded of the ongoing study, and of their commitment to the panel by email and by phone. More specifically, three statuses of panellists have been defined at the beginning of each study fieldwork:

-

Active – has responded to the preceding study.

-

Dozing off – non-respondent only to the preceding study.

-

Invisible – non-respondent to the two preceding studies in a row

All the non-respondents to a survey have been reminded by email two times. In addition, panellists in the dozing off and invisible categories have also been called back on the telephone—the former on the penultimate, and the latter on the second week of the fieldwork. The panellists were contacted using the phone numbers made available to panel managers, once on each number. Nonrespondents to more than two preceding studies in a row were moved into the “super invisible” category. They did not receive telephone reminders anymore but continued to receive email invitations and reminders. In addition, they were notified by postal mail about their initial commitment to the panel and invited to respond to oncoming survey invitations. If they remained nonrespondent to the following waves, they were thanked for their participation and removed from the panel. Figure 1 depicts the lifecycle of an ELIPSS survey.

In 2021, an experimental protocol was set up to test the efficacy of telephone callbacks to reduce non-response. As the beginning of the experiment coincided with a panel refreshment, the panellists were first divided into two categories: those who were present in the panel before the last recruitment, and those who were recruited recently. Then, within each category, panellists were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental treatments, thus forming 4 groups in total (see Table 1).

The treatment in Condition 2 (email + telephone) corresponded to the normal callback operating mode, whereas the treatment in Condition 1 (email only) was somewhat heterogeneous. Those who had participated in ELIPSS before 2020 had their telephone reminders suspended (at least some of them could have already received a telephone callback before the setting up of the experimental protocol), while those who were recruited in 2020 had never been called back on the telephone to remind them of an ELIPSS study.

Eight studies were conducted during the implementation of the experimental protocol. At the beginning of the first study, all the panellists were considered as systematically participating in the studies proposed to them. The panel was purged at that time from former inactive panellists when the new panellists were integrated. Hence, the first panellists populating the dozing off category appeared at the beginning of the second study, while the full range of statuses was available only at the beginning of the third. Therefore, the analysis featured in the following sections pertains to the response rates collected only during six out of the eight studies. The first two studies could also be considered as a period of dishabituation with regard to telephone callbacks for Condition 1 panellists recruited before 2020.

3. Analyses

3.1. Telephone callbacks

A significantly greater proportion of the invisible were effectively called back (χ²(1) = 33.8, p < 0.0001; see Table 2 for details). This could reflect the simple fact that the dozing off were called back later during the study fieldwork than the invisible, so they had more time to respond before the callback. A slightly greater proportion of the dozing off compared to the invisible responded to surveys following those callbacks, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (see Table 3 for details).

Given the difference of responses obtained from the dozing off and the invisible between groups 1 and 2 (137), the number of 853 callbacks issued for a total amount of 855€ (57 hours of work paid 15€ per hour), the estimated cost of one supplementary response was 6.2€.

Response behavior

From the protocol previously described, we observed the participation behavior of 1,919 panellists to six surveys, i.e., 10,978 decisions to respond to an ELIPSS survey (excluding the cases where panellists had been moved into the super invisible category). Besides our treatment, we took into consideration six other independent variables: the previous response pattern (status), the period of recruitment in the panel (recruitment wave), age (in seven groups), education (in four groups), gender, and area of residence (in five groups) to explain response behavior.

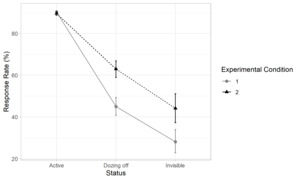

We fitted a logistic regression with robust standard errors to adjust for within-subject repeated measures of response. The results (see Table 4 for details) make it possible to confirm a strong and statistically significant principal effect of the panellists’ status (response rate of 89.9%, 54.3%, and 35.1% for the active, dozing off, and invisible, respectively) as well as a weaker principal effect of the experimental treatment (response rate of 85.3% and 82.9% for Condition 2 and 1, respectively) on the dependent variable.

As the interaction between those two variables was also significant, we focused on the analysis of that complex effect rather than on the principal effects of both variables. For that purpose, we conducted post-hoc pairwise Tukey comparisons of response propensity between the groups resulting from the interaction (see Figure 2, and Table 5 in the Appendix for details). We found that the active panellists had the strongest response propensity irrespective of the experimental treatment (response rate of 89.6% in Condition 2 vs. 90.2% in Condition 1) that, actually, made a difference only for the dozing off (62.9% in Condition 2 vs. 45% in Condition 1) and the invisible (44.1% vs. 28.1%).

In addition to the main effects of interest, several control variables also had a significant effect. Response propensity increased with age (odds ratio [OR] = 1.31, 95% confidence intervals [CI] [1.25, 1.37]) and decreased with level of education (OR = 0.9, 95% CI [0.84, 0.97]). Females were found more reactive to study invitations than males (84.8% vs. 83.4% response rate). The response rate of the panellists recruited before 2020 was better (85.6%) than that of those recruited shortly before the experiment (81.4%).

4. Discussion and conclusion

We analyzed the impact of telephone callbacks on ELIPSS panellists’ response propensity within a limited period of panel activity, while controlling for a set of behavioral and sociodemographic characteristics. The results of the experiment confirmed the effectiveness of telephone callback protocol in boosting response rates as opposed to mere email reminders of a pending survey and therefore limiting wave-specific nonparticipation. An effective response to a preceding study was the best predictor of responding to the current one, irrespective of whether the panellist could have been called back on the telephone to respond to one of the previous studies or not. Once this rhythm was broken as a study was not responded to, the probability of further nonresponse increased, and telephone callbacks became useful. However, even though the probability of response decreased for an invisible panellist (who missed the two preceding studies) compared to a dozing off (only one study missed), the effectiveness of telephone callbacks was similar for both statuses. Furthermore, we could also reproduce some effects known from the literature on survey and panel nonresponse, such that panellists’ age and level of education are generally correlated to their response rates and that females are slightly more committed than males.

From a practical standpoint, different retention strategies involving personal contact can further be conceived. For example, we could think about how to make inactive panellists (here, the super invisible category) renew their commitment. One can imagine a strategy consisting of contacting them after a longer delay (in the case of panels similar to ELIPSS, after missing more than four studies for example) in order to persuade them of the importance of regularly responding to surveys. Such an approach should be designed based on proven persuasion techniques. For example, benefits of participating should be emphasized, and inconveniences downplayed, social norms in favor of participating should be made salient, and the perceived control over one’s response behavior should be reinforced (Ajzen 1991). Once the intention to participate is reconfirmed by the panellist, appropriate implementation intentions techniques could also be envisaged (Gollwitzer and Sheeran 2006).

Otherwise, our results highlight the importance of panel refreshments aimed at completing the profiles that are the most prone to attrition. In fact, those profiles seem very hard to maintain in the long run, even with such costly and time-consuming approaches as telephone callbacks, unless those approaches are appropriately readjusted as suggested previously. On the other hand, panel managers should also be aware and careful not to produce Hawthorne effects (Dickson and Roethlisberger 2003) that could eventually affect response behavior of people targeted by exceptional procedures aimed at retaining them in the panel.

Despite their undoubted interest, the results of our study should be interpreted with caution because of the short period covered by the experimental treatments. In fact, within the current framework, one remains unable to make predictions about possible consequences of the wave-specific nonresponse such as attrition. For the same reason, panellists’ typology used in the analyses could also be considered as quite limited compared to some in-depth studies of panellists’ profiles (Lugtig 2014). Future research on similar topics should cover longer periods of data collection to overcome those limitations.

Acknowledgment

The research presented in this paper benefited from a grant (no. 20DATA-002-0/20DATA-002-1) of the French National Public Health Agency (Santé Publique France).